(click to play to video analysis)

Thoughts and discussions in economics, finance and history, with focus on China's interactions with the global economy.

The dollar and the euro are engaged in an ugly contest.

In a long slide since 2000, the dollar has lost 41% against the euro. After a brief rebound as investors sought safety during the worst of the financial crisis, the greenback again weakened through 2009. But that could change this year.

That might seem odd as, on the face of it, there is little to recommend the dollar. A fed-funds target rate hovering at around zero, quantitative easing and ballooning deficits all serve to undermine the currency. Economic data, especially in consumer-sensitive areas like housing and employment, remain weak.

Ugly as that is, Europe is no model of perfection either. Greece, the obvious blemish, points to a deeper malaise. As Brown Brothers Harriman & Co. says, incomplete political union leaves the euro zone without effective mechanisms to enforce fiscal discipline in member states.

Other countries—like Greece—have lost competitiveness over the past decade but could not devalue, and relied on fiscal expansion instead. If Greece calls for a bail-out, countries like Germany will have to weigh the risks of raising moral hazard versus the risks of destabilizing markets by standing firm—an unpalatably Lehman-like quandary. The need for more rigorous fiscal policing by definition suggests further erosion of member-state sovereignty will be required, setting the stage for protracted political wrangling.

China's artificially low renminbi may be compounding the euro zone's problems. Lombard Street Research reckons European businesses bear the brunt in terms of loss of market share in international trade.

China's recent moves to tighten monetary policy might suggest some relief on this front. But the more pertinent effect, from a currency perspective, is to raise anxieties in financial markets—as observed in recent stock sell-offs and the jump in volatility measures like the VIX index. As the experience of late 2008 showed, if things turn ugly, investors tend to close their eyes and embrace the dollar.

The Federal Reserve's blowout 2009 profit is no reason to cheer. Rather, it is a reminder of the dangers inherent in the extraordinary policies the central bank has pursued during the credit crunch.

![[FEDHERD]](http://sg.wsj.net/public/resources/images/MI-BA800A_FEDHE_NS_20100112170742.gif)

Last year, the Fed earned $52.1 billion, with most of that income coming from interest-payments on bonds that it bought during the year to shore up the economy and credit markets.

Anyone with access to printing presses could have racked up similar gains. But the Fed's purchases leave it exposed. Its assets are 43 times its capital, compared with 15 times at Goldman Sachs. As a result, its equity could be wiped out by just a 2.8% drop in the value of its Treasurys and securities issued by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. True, the Fed could hold on to those securities and ride out any losses, and retain earnings to boost capital, but what self-respecting central bank wants to risk a negative net worth?

Even the fact that the Fed is, as usual, paying most of its profit to the Treasury isn't good news. It means the Treasury is paying almost no interest on a large slug of debt purchased by the Fed. That can only chip away further at fiscal discipline.

Be careful what you wish for. Six weeks ago, Jean-Claude Juncker, who chairs the group of euro-zone finance ministers known as the Eurogroup, complained that the euro was overvalued. Since then it has fallen 6.6% against the dollar. But Mr. Juncker can't be too happy. Persistent fears about Greece's fiscal situation have turned trade in the euro into a vote on the currency bloc's credibility.

The euro now trades just below $1.41, versus a peak on Nov. 25 last year of $1.51. Even that decline hasn't done much to erase the currency's strength, accumulated over much of the previous decade: in mid-December, at $1.45, the European Commission warned that the euro was overvalued on a real effective basis by 7% to 8%.

![[EUROHEARD]](http://sg.wsj.net/public/resources/images/MI-BA955_EUROHE_NS_20100121211306.gif)

A range of factors are weighing on the euro. Some seem likely to be transitory: Fears about China's moves to rein in credit growth seem more aimed at trying to head off domestic inflation before it gets out of control, and thus should be good for global risk appetite in the long run. But others are more deeply entrenched. The European Central Bank has warned that the recovery in Europe will be gradual, and many expect the bank to increase rates later than the U.S. Federal Reserve or the Bank of England.

The key driver, however, has been the strains within the euro zone that Greece's struggle to rein in its public finances has brought into the spotlight. The euro's fall has come in lockstep with a rise in the cost of insuring Western European sovereign debt against default, as measured by the Markit iTraxx SovX index, which hit a record high of 0.84 percentage point points Wednesday, up from 0.57 at the start of December. Higher yields and a weaker currency might help to lure foreign buyers of bonds, something Greece is desperate to do. But higher yields are being interpreted as a sign of distress, rather than an opportunity. Hawkish ECB rhetoric warning that there will be no fudge on euro-zone rules to aid Greece are intensifying the pressure, even if his should be good for the euro's credibility in the longer term.

Further pressure seems likely as a result—at least in the short-term. Barclays technical analysts warn that a break below $1.4050 could lead to a dip as far as $1.3730; Citigroup said in January the euro could drop as far as $1.35. One worry now is contagion: If investors become concerned about other euro-zone countries such as Portugal, Spain or Ireland, more may decide to dump the single currency.

Innovation and Economic Growth from Innovation Economy on Vimeo.

What are we smoking, and when will we stop?

A nationwide survey last year found that investors expect the U.S. stock market to return an annual average of 13.7% over the next 10 years.

Robert Veres, editor of the Inside Information financial-planning newsletter, recently asked his subscribers to estimate long-term future stock returns after inflation, expenses and taxes, what I call a "net-net-net" return. Several dozen leading financial advisers responded. Although some didn't subtract taxes, the average answer was 6%. A few went as high as 9%.

We all should be so lucky. Historically, inflation has eaten away three percentage points of return a year. Investment expenses and taxes each have cut returns by roughly one to two percentage points a year. All told, those costs reduce annual returns by five to seven points.

So, in order to earn 6% for clients after inflation, fees and taxes, these financial planners will somehow have to pick investments that generate 11% or 13% a year before costs. Where will they find such huge gains? Since 1926, according to Ibbotson Associates, U.S. stocks have earned an annual average of 9.8%. Their long-term, net-net-net return is under 4%.

All other major assets earned even less. If, like most people, you mix in some bonds and cash, your net-net-net is likely to be more like 2%.

The faith in fancifully high returns isn't just a harmless fairy tale. It leads many people to save too little, in hopes that the markets will bail them out. It leaves others to chase hot performance that cannot last. The end result of fairy-tale expectations, whether you invest for yourself or with the help of a financial adviser, will be a huge shortfall in wealth late in life, and more years working rather than putting your feet up in retirement.

Even the biggest investors are too optimistic. David Salem is president of the Investment Fund for Foundations, which manages $8 billion for more than 700 nonprofits. Mr. Salem periodically asks trustees and investment officers of these charities to imagine they can swap all their assets in exchange for a contract that guarantees them a risk-free return for the next 50 years, while also satisfying their current spending needs. Then he asks them what minimal rate of return, after inflation and all fees, they would accept in such a swap.

In Mr. Salem's latest survey, the average response was 7.4%. One-sixth of his participants refused to swap for any return lower than 10%.

The first time Mr. Salem surveyed his group, in the fall of 2007, one person wanted 22%, a return that, over 50 years, would turn $100,000 into $2.1 billion.

Does that investor really think he can get 22% on his own? Apparently so, or he would have agreed to the swap at a lower rate.

I asked several investing experts what guaranteed net-net-net return they would accept to swap out their own assets. William Bernstein of Efficient Frontier Advisors would take 4%. Laurence Siegel, a consultant and former head of investment research at the Ford Foundation: 3%. John C. Bogle, founder of the Vanguard Group of mutual funds: 2.5%. Elroy Dimson of London Business School, an expert on the history of market returns: 0.5%.

Meanwhile, I asked Mr. Salem, who says he would swap at 5%, to see if he could get anyone on Wall Street to call his bluff. In exchange for a basket of 51% global stocks, 26% bonds, 13% cash and 5% each in commodities and real estate—much like a portfolio Mr. Salem oversees—the institutional trading desk at one major investment bank was willing to offer a guaranteed rate, after fees and inflation, of 1%.

All this suggests a useful reality check. If your financial planner says he can earn you 6% annually, net-net-net, tell him you'll take it, right now, upfront. In fact, tell him you'll take 5% and he can keep the difference. In exchange, you will sell him your entire portfolio at its current market value. You've just offered him the functional equivalent of what Wall Street calls a total-return swap.

Unless he's a fool or a crook, he probably will decline your offer. If he's honest, he should admit that he can't get sufficient returns to honor the swap.

So make him explain what rate he would be willing to pay if he actually had to execute a total return swap with you. That's the number you both should use to estimate the returns on your portfolio.

Beijing has big plans for wind power as a renewable energy of the future, but China may already have too much of a good thing.

At home, China's power-transmission infrastructure can't handle the intermittent electricity supply already being generated from wind. It is estimated that 30% of last year's wind-power supply went unused.

Despite that bottleneck, Beijing wants more. The government hopes to see 100 gigawatts of wind-power capacity installed in China by 2020, a more-than-eightfold increase from 2008, making wind the third most important source of power in China behind coal and hydroelectric. Even by next year, the amount of wind-power equipment being made will be twice what the nation can install, according to the central government.

That has implications abroad. Foreign rivals are raising concerns that Chinese producers will export their excess capacity at cheap prices. Wind power was one of the industries cited last week by the European Chamber of Commerce in China as likely to stir trade tensions.

The Chinese companies have already proven to be formidable competitors. Domestic producers have seen their Chinese market share blossom to nearly 60% collectively. That's largely at the expense of foreign players like Vestas Wind Systems, Gamesa and General Electric, which were dominant there just five years ago.

Critics suggest an implicit "Buy China" policy has helped the domestic players, but it's clear, too, that they have competed strongly on price. Data from analysts IHS CERA show Chinese equipment suppliers sell their turbines for almost two-thirds of the price of foreign competitors.

Not surprisingly, the number of players in the wind-power equipment sector has mushroomed, drawn to the sector by talk of greater reliance on renewable energy. Four companies accounted for more than 90% of the wind-turbine-manufacturing market in 2004. Now, 12 industry leaders account for about the same proportion, according to IHS CERA. Around 70 smaller firms are also active.

As local players duke it out, consolidation is likely in the near term. That will likely benefit the domestic industry leaders: Sinovel Wind, Xinjiang Goldwind Science & Technology and Dongfang Electric.

All this is happening in a market that is already uncertain as governments debate climate-change initiatives. Potential problems have already marred a United Nations wind-power credit program, for example.

The world may want China to commit to a greener future, but it's rapidly finding out that the push can come with some unwanted side effects.

Few would have dared predict 12 months ago that markets would rebound so strongly. Most major stock markets ended 2009 at or around their highs for the year. Both the S&P 500 and FTSE Eurotop 100 rallied 24% over the year, while corporate-bond markets and commodities also staged rallies.

But what about 2010? Most economists expect the recovery to be sustained, albeit with fewer opportunities, to make significant gains. But any optimism needs to be tempered by caution. The global economy still is exposed to significant risks. Here are four:

• Sovereign risk: The Dubai World debt default and Greek fiscal crisis were reminders that vast amounts of debt remain outstanding, with implicit or explicit guarantees from friendly sovereign nations. Will those nations be willing to stand behind the debt? The market is betting Abu Dhabi will bail out Dubai and the euro zone won't allow any of its members to default, even if the pain spreads to other highly indebted states such as Ireland and Spain. A more-pressing case may be the U.K., whose fiscal position is the worst in the industrialized world and which enjoys no implicit guarantee.

![[RISKHERD]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/MI-BA620_RISKHE_NS_20100101221117.gif)

• Exit strategies: The Federal Reserve and European Central Bank both have set out plans to withdraw much of the emergency liquidity supplied during the crisis. The Bank of England also is expected to stop buying U.K. government bonds in February. That could pave the way for considerable bond-market volatility, because central-bank programs have helped push down yields across all asset classes. Investors should be wary of parallels with 1994, when an unexpected U.S. interest-rate increase triggered a bond-market rout. On that score, they should be watching for any sniff of rising inflation.

• Slow growth: Much of the optimism in the markets is based on expectations that global growth will be robust enough to speed up the process of deleveraging among overindebted Western economies. One risk to this outlook is that a combination of fiscal tightening and monetary-policy exit strategies leads to a "double-dip" recession. Another is that U.S. unemployment will be slow to fall while European unemployment continues to rise, leading to weak consumer demand. A slower-than-expected recovery would lead to higher bank-loan impairments and put more pressure on government fiscal deficits.

• Bank balance sheets: The global banking system is in better health than a year ago, bolstered by large injections of equity and strong earnings. But trading desks could be vulnerable to any asset-price corrections. And doubts remain whether banks are facing up to the full extent of losses on loan books. The practice of "amend, extend and pretend," particularly in relation to commercial property, may be concealing the true scale of bad debts. A sharp rise in bond-market yields also would put pressure on bank-funding costs.While 2010 is unlikely to bring anything like this year's gut-wrenching volatility, investors shouldn't expect it all to be plain sailing.

More importantly, the amount of time people devote to LinkedIn is a fraction of the time people spend on some other social sites. Visitors spent about 13 minutes on average at LinkedIn during October, while Facebook users logged about 213 minutes and MySpace users spent 87 minutes, according to research firm comScore, which measured the behavior of global users 15 years and older.

Read full text here.

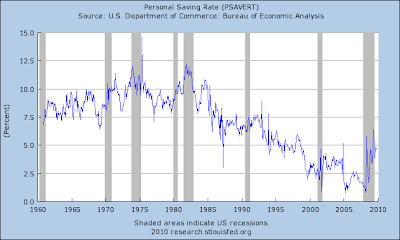

U.S. consumers in November reduced borrowing by the most on record, cutting credit card use by nearly 20% even as the economy recovers.

Consumer credit outstanding decreased at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 8.5% to $2.465 trillion.

The $17.5 billion tumble is the largest since the Fed began keeping records in 1943.

Economists surveyed by Dow Jones Newswires had forecast a $6 billion drop in consumer credit. It was the 10th drop in a row. Consumer credit fell $4.2 billion in October.

Household debt began dropping in the summer of 2008. The financial crisis struck and sparked panic, startling people into taking a serious look at their balance sheets.

While weaning oneself off debt is considered good from a personal finance viewpoint, widespread deleveraging among U.S. households has reduced spending, an omen for the economy.

Consumer spending makes up two-thirds of gross domestic product, the measure of economic activity. Their spending needs to grow for the economy to recover into 2010. But some banks are making it hard for people to get loans. And the job market hasn't healed; data Friday showed payrolls fell in December, even more than expected.

Retail sales rose strongly in October and November. The Fed report Friday suggested people are dipping into savings to support their spending. Revolving credit, or credit-card use, fell by $13.7 billion to $874.0 billion. That was a record 14th straight drop. At 18.5%, the fall was the biggest since December 1974. Credit-card use fell 9.9% in October and 10.5% in September.

Non-revolving credit, including automobile and mobile home loans, decreased in November by 2.9%, or $3.8 billion, to $1.591 trillion.

The consumer-credit data exclude home mortgages and other real estate-secured loans. These tend to be highly volatile from month to month and are frequently revised. But the report still has interesting details on how Americans finance their lifestyles.

THE effect of free money is remarkable. A year ago investors were panicking and there was talk of another Depression. Now the MSCI world index of global share prices is more than 70% higher than its low in March 2009. That's largely thanks to interest rates of 1% or less in America, Japan, Britain and the euro zone, which have persuaded investors to take their money out of cash and to buy risky assets.

For all the panic last year, asset values never quite reached the lows that marked other bear-market bottoms, and now the rally has made several markets look pricey again. In the American housing market, where the crisis started, homes are priced at around fair value on the basis of rental yields, but they are overvalued by almost 30% in Britain and by 50% in Australia, Hong Kong and Spain.

Stockmarkets are still shy of their record peaks in most countries. The American market is around 25% below the level it reached in 2007. But it is still nearly 50% overvalued on the best long-term measure, which adjusts profits to allow for the economic cycle, and is on a par with two of the four great valuation peaks in the 20th century, in 1901 and 1966.

Central banks see these market rallies as a welcome side- effect of their policies. In 2008, falling markets caused a vicious circle of debt defaults and fire sales by investors, pushing asset prices down even further. The market rebound was necessary to stabilise economies last year, but now there is a danger that bubbles are being created.

ATLANTA -- Wall Street investors may be breathing a sigh of relief as the financial crisis fades, but academic economists gathered here for the annual meeting of the American Economic Association say we're nowhere close to making sure it won't happen again.

Over the past few days, economists here highlighted the many ways in which the lessons of the crisis have yet to sink in. Few think the U.S. and other governments have made needed repairs to the financial regulatory system. And some suggest governments' response has increased the chances of a repeat, making the banking system more crisis-prone, putting new strains on institutions such as the Federal Reserve and stretching government finances closer to the breaking point.

![[Unsolved Problems]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/NA-BD206_NOTDON_NS_20100105185239.gif)

"Our response has made us more vulnerable to a bigger crisis," said Tom Sargent, a New York University economist. "It's distressing."

Banks present the most immediate worry. By providing massive bailouts to commercial banks and securities firms, the logic goes, governments have given bank executives a sort of catastrophe insurance -- and an incentive to take even greater risks than they did before the crisis. But it could take years for policy makers to impose the controls, such as tougher capital requirements, that would prevent the pain from spreading to taxpayers and the broader economy next time the banks get into trouble.

"If the banks really feel that they are insured, then we have a dangerous situation," said Stanford University's Robert Hall, the association's president. "The incentives are to take a very risky position. They get to pocket it if they win and it's the federal government's problem if they lose."

Policy makers find themselves in a tough position. They can't impose controls immediately, for fear they would curb the lending crucial to a sustainable economic recovery. But as the banks regain strength, the political opportunity to create a new financial architecture could slip away.

"You have only a small window in which you can really change things," said Markus Brunnermeier, of Princeton University. "It's closing already."

The crisis isn't over for banks. The worst-case scenarios in last year's stress tests, which restored the market's confidence in U.S. banks, included only two years' worth of losses. But banks are likely to face losses for many years to come as foreclosures mount and the commercial real-estate market sours.

"If the U.S. government could credibly say [to banks]: We'll never bail you out again, it [the banking system] would collapse," said Kenneth Rogoff, of Harvard University.

To quicken the banks' return to health, Princeton's Mr. Brunnermeier believes governments should place much harsher limits on cash dividend and bonus payouts, which deplete the capital banks need to absorb the losses and keep lending.

"I don't think there's enough forcefulness from the administration on this," he said. "If Goldman Sachs is paying these huge bonuses, the other banks are forced to do so as well."

Others fretted about the lack of a game plan for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the money-losing mortgage giants -- known as government-sponsored enterprises -- that are now absorbing huge sums of taxpayer money as part of the U.S. government's efforts to keep the mortgage market functioning. When long-term interest rates rise, as they inevitably will, said Anthony Sanders, of George Mason University, "We're going to see tremendous losses taken on the bank balance sheets and [those of the GSEs]."

"The GSE structure must be ended because it creates inevitable failure based on the incentives," said Dwight Jaffee, of the University of California at Berkeley. But he and his peers differed on the best solution. Mr. Jaffee called for the government to buy mortgages and package them into securities, as Fannie and Freddie do, but only temporarily; eventually, that task should be turned over to the private sector.

A pair of Federal Reserve economists, Diana Hancock and Wayne Passmore, emphasizing that they weren't expressing the Fed's official view, suggested the government should explicitly guarantee not only mortgages but other financial instruments against a catastrophe with a new insurance fund, financed by premiums similar to the one used to insure bank deposits.

Economists also expressed concern about the extent to which the unprecedented measures taken by the government and Fed could weaken them as a backstop in the future. The Fed's massive interventions have exposed it to greater financial and political risk, both of which could lessen its ability to step in and calm markets. And the huge costs of financial and economic bailouts have put added burdens on the finances of advanced-economy governments around the world.

In the next few years, for example, the gross government debt of both the U.S. and the U.K. will exceed 90% of their annual economic output, an event that could both spook investors and seriously impair economic growth.

When advanced countries cross the 90% threshold, their annual growth tends to be about one percentage point lower, said Mr. Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart of the University of Maryland.

"This is very troubling for the U.S. and other advanced economies," said Ms. Reinhart.

AEA Economics Humor Session:

Sunday Jan 3 at 8 pm at the Atlanta Marriott Marquis:

Academic economists gather in Atlanta this weekend for their annual meetings, always held the first weekend after New Year's Day. That's not only because it coincides with holidays at most universities. A post-holiday lull in business travel also puts hotel rates near the lowest point of the year.

Economists are often cheapskates.

The economists make cities bid against each other to hold their convention, and don't care so much about beaches, golf courses or other frills. It's like buying a car, explains the American Economic Association's secretary-treasurer, John Siegfried, an economist at Vanderbilt University.

"When my wife buys a car, she seems to care what color it is," he says. "I always tell her, don't care about the color." He initially wanted a gray 2007 Mercury Grand Marquis, but a black one cost about $100 less. He got black.

Some of the world's most famous economists were famously frugal. After a dinner thrown by the British economic giant John Maynard Keynes, writer Virginia Woolf complained that the guests had to pick "the bones of Maynard's grouse of which there were three to eleven people." Milton Friedman, the late Nobel laureate, routinely returned reporters' calls collect.

Children of economists recall how tightfisted their parents were. Lauren Weber, author of a recent book titled, "In Cheap We Trust," says her economist father kept the thermostat so low that her mother threatened at one point to take the family to a motel. "My father gave in because it would have been more expensive," she says.

"Where do I begin?" says Marisa Kasriel when asked about the lengths to which her father, Northern Trust Co. economist Paul Kasriel, will go to save a buck: private-label groceries, off-brand tennis shoes and his 1995 Subaru, with a piece of electrical tape covering the "check engine" light.

Mr. Kasriel says he buys off-brand shoes "so that my lovely children could have Nikes."

David Colander, an economist at Middlebury College in Vermont, says his wife -- his first one, that is -- was miffed when he went shopping for the cheapest diamond. Economist Robert Gordon, of Northwestern University, says he drives out of his way to go to a grocery store where prices are cheaper than at the nearby Whole Foods, even though it takes him an extra half hour to save no more than $5.

Mr. Gordon, however, is no ascetic. He, his wife and their two dogs live in a 11,000-square-foot, 21-room 1889 mansion on the largest residential lot in Evanston, Ill., outside Chicago.

"The house is full, every room is furnished, there are 72 oriental rugs and vast collections of oriental art, 1930s art deco Czech perfume bottles and other nice stuff," he says.

Some economists may be cheap, at least by the standards of other people, because of their training or a fascination with money and choices that drives them to the field.

In recent research, University of Washington economists Yoram Bauman and Elaina Rose found that economics majors were less likely to donate money to charity than students who majored in other fields. After majors in other fields took an introductory economics course, their propensity to give also fell.

"The economics students seem to be born guilty, and the other students seem to lose their innocence when they take an economics class," says Mr. Bauman, who has a stand-up comedy act he'll be doing at the economists' Atlanta conference Sunday night. Among his one-liners: "You might be an economist if you refuse to sell your children because they might be worth more later."

Economists long have studied "free riders," the sort of people who take more than their fair share of something when circumstances permit. Think of the person who orders the most expensive entr[eacute]e at a restaurant, knowing that the check will be shared equally among companions.

University of Wisconsin sociologists Gerald Marwell and Ruth Ames, in a 1981 paper, found that in experiments, economics students showed a much higher propensity to free ride than other students. In questioning after the experiment, the sociologists found that for many of the economics students, the concept of investing fairly "was somewhat alien."

Cornell University economist Robert Frank, working with a pair of psychologists, mailed questionnaires to college professors asking them to report the annual amount they gave to charity. Their 1993 paper reported that 9.1% of the economists gave no money at all -- more than twice as many holdouts as in any other field.

The professors also ran an experiment in which participating Cornell undergraduate students could get a higher payoff if they agreed to have their partner get less. Economics majors were more likely to go for the higher payoff, they found.

Some dispute the notion that economists tend to be skinflints. "They aren't cheap," but they are concerned with a loss of economic efficiency, says Betsey Stevenson, an economist at the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School. "That means that they often fail to do the nice little social gifts that seem wasteful to economists."

And the principles that can make economists seem cheap sometimes lead them to hire help, because they are taught to value their own time.

Ms. Stevenson and Justin Wolfers, also of the Wharton School, gave a friend $150 to hire movers instead of helping him themselves. Harvard University economist David Laibson pays to have a driver pick up his sister from the airport rather than driving himself.

Stanford University economist Robert Hall, incoming president of the American Economic Association, values his time so highly that his wife, economist Susan Woodward, occasionally puts her foot down. "Bob doesn't see why we can't just hire people to trim the Christmas tree," she says. "I tell him that's not what it's supposed to be about."

Given their understanding of the odds of gambling, economists seldom frequent casinos, which is one reason the meeting isn't held in Las Vegas. A decade ago, a hotel sales representative showed Mr. Siegfried a chart showing how little economists gambled compared to other people, he says.

The American Economic Association meetings, however, have been held in New Orleans, which has a few casinos.

One year, Yale University economist Robert Shiller, who'd never gambled in his life, found himself at a casino there. He says that was because Wharton economist Jeremy Siegel realized that by using coupons offered to conventioneers, they could take opposing bets at the craps table with a 35 out of 36 chance of winning $12.50 each. Over two nights, Mr. Shiller netted $87.50.

He hasn't gambled since.

Write to Justin Lahart at justin.lahart@wsj.com

Joseph Stiglitz didn't mince words when he kicked off the American Economic Association's annual meeting in Atlanta on Saturday. The Nobel laureate, who teaches at Columbia University, launched into a blistering attack on fellow economists for building models that rely on rational behavior when the financial crisis offers so much evidence of irrationality.

Wall Street also got a broadside. To Mr. Stiglitz, the purpose of a financial system is "to manage risk and allocate capital at low transaction costs." What actually happened? "They misallocated capital. They created risk. And they did it at enormous transaction costs."

As for the bonus culture, Mr Stiglitz called time on the myth that Wall Street is populated by the best and the brightest who deserve their big paydays. "When I look at the salaries some of our 'B' students got [on Wall Street], it doesn't correspond to their innate ability."