By Ricardo Hausmann

Financial Times Jan. 30, 2008

The same voices that supported tough macroeconomic policies to deal with the excesses of spending and borrowing in east Asia, Russia and Latin America are today pushing for a significant relaxation in the US to deal with the so-called subprime crisis. Interest rates should be slashed quickly and $150bn put into taxpayers' pockets by April at the latest, they say. The Fed cut by another half-point on Wednesday.

The goal seems to be to avoid a 2008 recession at all costs. As Larry Summers, former Treasury secretary, put it, failure to act would make Main Street pay for the sins of Wall Street.

It is easy to lose sight of the overall picture. Main Street consumers have overspent and over-borrowed and are unable to meet their obligations. The fact that households may have so behaved because they were enticed by "teaser loans" does not change the facts; it only assigns blame. Consumption has been above sustainable levels and needs to adjust down, whatever view one has about the responsibility of adults over their financial decisions.

The adjustment of private consumption to sustainable levels is necessary, but is likely to have a negative influence in the short run on the growth of aggregate demand, of which it represents more than 70 per cent. It is hard for this adjustment to take place without bringing down the rate of growth of gross domestic product, possibly to negative numbers.

It will also lower the US external deficit and put downward pressure on world growth. That is a consequence of the imbalances accumulated over five years of unprecedented world growth. Returning to a sustainable path is good for the US and the world economy over any horizon that assigns some value to what happens after 2008. Sustainable growth is not the consequence of an unsustainable consumption boom but of the progress and diffusion of science, technology and innovation – which show no sign of slowing down.

An efficient adjustment to the US over-consumption imbalance (and Chinese under-consumption) in a way that does not hurt longer-term growth should be based on compensating for the decline of US consumption with an increase in domestic investment and in consumption abroad. It should not be based on giving the US consumer more rope with which to hang himself.

Hence, macroeconomic policy should not be based on a panicky attempt to avoid a 2008 recession at all costs but on a forward-looking strategy that achieves the needed reduction in consumption at the lowest cost in terms of the stable growth. This is not achieved by giving US households a $1,000 cheque by April, a trick that no macroeconomic textbook would argue is particularly effective. If there is fiscal room – a big if, given the weak structural position of the US government and its likely cyclical worsening – it would be better spent in accelerating investments in plant and equipment via accelerated depreciation schemes, to improve the capacity of the economy to keep on growing after the crisis.

The logic behind monetary easing is also suspect. Much of it is automatic, as central banks pump in money just to keep interest rates steady. It is understandable that politicians facing a November election and bankers with a lot of their money at stake should feel that this is the worst crisis ever and have an obvious interest in exaggerating the consequences for Main Street.

They all assume that if banks lose capital, they will stop lending. This is what happens in developing countries because of incomplete financial markets, but is not what one would expect in the world's most sophisticated capital market. In fact, bank capital has already been lost and the solution is not to put more air into the bubble but to put more capital into banks. This is already happening: Citibank, UBS, Merrill Lynch and Morgan Stanley have raised more than $100bn from foreign investors and sovereign wealth funds. Authorities might use their moral suasion to accelerate this process.

The US should face its need for adjustment with courage and reason, not fear. It should stop behaving as the whiner of first resort, ready to waste all its dry powder on a short-sighted attempt to prevent a 2008 recession. Many poorer countries with weaker markets and institutions have survived and benefited from an adjustment that involves a year of negative growth. Faster bank recapitalisation, fiscal investment stimulus and international co-ordination should be first on the policy agenda.

The writer is the director of Harvard University's Center for International Development

Thursday, January 31, 2008

Stop behaving as whiner of first resort

Wednesday, January 30, 2008

Fed Cut Funds Rate to 3%

Release Date: January 30, 2008

For immediate release

The Federal Open Market Committee decided today to lower its target for the federal funds rate 50 basis points to 3 percent.

Financial markets remain under considerable stress, and credit has tightened further for some businesses and households. Moreover, recent information indicates a deepening of the housing contraction as well as some softening in labor markets.

The Committee expects inflation to moderate in coming quarters, but it will be necessary to continue to monitor inflation developments carefully.

Today's policy action, combined with those taken earlier, should help to promote moderate growth over time and to mitigate the risks to economic activity. However, downside risks to growth remain. The Committee will continue to assess the effects of financial and other developments on economic prospects and will act in a timely manner as needed to address those risks.

Voting for the FOMC monetary policy action were: Ben S. Bernanke, Chairman; Timothy F. Geithner, Vice Chairman; Donald L. Kohn; Randall S. Kroszner; Frederic S. Mishkin; Sandra Pianalto; Charles I. Plosser; Gary H. Stern; and Kevin M. Warsh. Voting against was Richard W. Fisher, who preferred no change in the target for the federal funds rate at this meeting.

In a related action, the Board of Governors unanimously approved a 50-basis-point decrease in the discount rate to 3-1/2 percent. In taking this action, the Board approved the requests submitted by the Boards of Directors of the Federal Reserve Banks of Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Cleveland, Atlanta, Chicago, St. Louis, Kansas City, and San Francisco.

Tuesday, January 29, 2008

(green: core inflation red: headline inflation)

see Bloomberg article on the same topic.

Let's Get Real About the Economy

Like stopped clocks that are right twice a day, the Greek chorus of perennial economic pessimists is chortling. At last, their Cassandra-like chanting has moved to center stage, amplified by the megaphone of last week's Davos gabfest. Nouriel Roubini, a New York University economist, sees a recession that will be "ugly, deep and severe." From Morgan Stanley's Stephen Roach: a potential economic "Armageddon" (a 2004 warning). Even the esteemed George Soros calls the current situation "the worst market crisis in 60 years."

Worse than the early '80s, when wildly exuberant lending thrust a thousand savings and loans into insolvency, and some major U.S. bank stocks plunged to single digits? Worse than 1981, when the Federal Reserve drove its key interest rate to 19% in an effort to staunch inflation? Remember the 1970s, when our economy was mired in stagflation? More painful than the dot-com hangover -- hardly a distant memory -- when the Nasdaq fell by 78% amidst widespread corporate bankruptcies? Let's get real.

![[Get Real!]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/ED-AH013_rattne_20080128174755.jpg)

Make no mistake, the U.S. economy is weak and getting weaker. Recession odds have elevated to Condition Red. And hard experience confirms that detecting downturns is far easier through a rearview mirror than through the windshield. But the probability remains that what our economy faces is less a plunge into the dark ages than a cyclical purging of excesses -- perhaps akin to the eight-month recession in 2001.

While the suddenness of the slowdown and extent of the turmoil in financial markets surprised many, the inevitability of a correction should have been evident. We've been aware for years that housing prices had soared well above their historic relationship to personal income. Americans were consuming beyond their means. Risk premiums -- the extra amount that investors get paid for buying paper other than Treasuries -- had fallen to record low levels that were clearly unsustainable. As those bubbles continued to inflate, we've known that the magnitude of the inevitable correction was growing.

It's easy to understand the fear that has enveloped our financial system, a fear grounded in the complexity and lack of transparency associated with the rise of increasingly esoteric derivatives with equally opaque names -- credit default swaps, CDOs, RMBSs and the like. But remember that the same derivatives that are now terrifying even major financiers are what have increasingly allowed banks to spread risk in a way that was never before possible.

Some of that risk was exported. That's why financial institutions across the world and even small towns in Norway are feeling the pain of subprime losses in the U.S. while our banks remain solvent, able to absorb their portion of the write downs. Contrast that to the consequences of the bout of overeager lending two decades ago, when major institutions like the Bank of New England went bankrupt and still larger banks nearly toppled.

So pronouncing the demise of the world's most productive economy is surely premature. Count among our other blessings a flexibility that has kept inflation low and given the Federal Reserve the scope to reduce interest rates without triggering inflationary fears. Even as rates have been lowered by 1.75 percentage points since last summer, inflationary expectations, as measured by Treasury Inflation Protected Securities, have slid (from 2.7% in June to around 1.8% today).

Compare that to Europe, where a stubbornly higher inflation rate has tied the hands of the European Central Bank. Would we really prefer to trade our economy for that of old Europe?

Accompanying the cries of the Cassandras has been another (sometimes overlapping) chorus of diatribes aimed at policy makers working to soften the pain of the adjustment process. Many of those jeremiads have been aimed at the Federal Reserve for having acted either too quickly or too slowly and, of course, for having created the problem in the first place by keeping interest rates too low for too long.

Anyone can call plays from the bleachers. But just as we don't stand over doctors in an emergency room, we need to lay off the Federal Reserve and its chairman, Ben Bernanke. No doubt, history will find some fault with Mr. Bernanke's real-time decision making. But given the uncertain and fast changing dynamics, the Fed should be commended, not demeaned, for its actions thus far.

At the same time, monetary policy can't by itself provide the spark that the economy needs. For one thing, relying completely on lower interest rates jeopardizes the progress that's been made since last summer in convincing markets that, yes, bad investment decisions will lead to losses. For another, monetary policy, which operates through lower interest rates, aids some -- but not all -- corners of the economy.

That's why we need to get behind last week's remarkable agreement between the White House and Democratic lawmakers on a stimulus package of tax cuts and rebates. Instead of yet another round of carping, congratulations should be offered, particularly to Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, for bridging difficult partisan differences.

No doubt, anyone could find fault with aspects of the package. For my part, I'd happily part with the ineffective accelerated depreciation and add a dollop of extended unemployment benefits. But of all the stimulus measures that have been assembled in our Washington sausage factory in past decades, this may well be the best, and the Senate needs to get over its hurt feelings about being left out of the negotiations.

This package need not be the end of our efforts to address our economic challenges, particularly the plight of homeowners. While the proposed legislation offers some hope for easing the mortgage crunch, more should be done.

In particular, we should reach back to the Depression and consider resurrecting the Home Owners' Loan Corporation. Created in 1933, that long-forgotten agency bought defaulted mortgages from savings-and-loan institutions at discounts to face value and then negotiated new terms with stretched homeowners to avoid foreclosure. By the time it finally closed down in 1951, the HOLC had aided one in five mortgaged dwellings and had even turned a small profit for the government.

We also should reform the patchwork of government regulators overseeing our financial institutions, to provide more coherence. While Alan Greenspan's Fed shouldn't be blamed for keeping rates low for too long (would we really have wanted slower growth these last five years?), it did ignore its responsibilities to regulate predatory lending. (Too much Ayn Rand and not enough FDR.) Additionally, with the internalization of financial markets, attention should be paid to Mr. Soros's excellent suggestion of more globally coordinated regulation.

Ironically, America's most serious economic challenges are almost surely the ones currently receiving the least amount of attention. Let's not forget that income inequality has risen to record and unacceptable heights. Nor should we lose sight of vast unfunded future obligations -- $50 trillion, by some government estimates -- for social welfare programs, particularly Medicare. Finally, as presidential candidates on the campaign trail remind us regularly, we have important unmet needs, ranging from health care to infrastructure.

While further stresses are inevitable as the adjustment process continues, our economic bedrock remains fundamentally strong. We have the means to continue to prosper, as long as we don't panic just when we should be getting down to work.

Mr. Rattner is managing principal of the private investment firm Quadrangle Group LLC.

--

**************************************

Paul D. Deng

Department of Economics

Brandeis University

IBS, MS 032

Waltham, MA 02454

http://www.pauldeng.com

Bernanke might will be a hero

It's Not Time To Judge

Bernanke YetBy JON HILSENRATH

January 29, 2008; Page C1, WSJBen Bernanke can't get a break.

Two weeks ago, the Federal Reserve chairman's critics complained he was standing idly by while the markets sank, and they clamored for more-aggressive action. Last week, when he did what they asked, they called him a pawn of fickle investors. Had he done nothing, the same critics probably would have said he was ignoring the potential economic damage of a stock-market collapse.

![[AOT]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/MI-AO856_AOT_20080128184433.gif)

In the end, all this hand-wringing about Mr. Bernanke's style and demeanor will be long forgotten if the Princeton professor gets his economics right. He's betting he can head off a recession by quickly lowering interest rates, possibly again tomorrow after the Fed meets. And he's betting he can do it without igniting inflation.

It's a stark choice and stands in clear contrast to his counterpart at the European Central Bank, Jean Claude Trichet. Mr. Trichet, who says he's more worried about inflation, hasn't moved rates at all.

It probably doesn't help Mr. Bernanke that he has to manage the situation while his former boss, Alan Greenspan, and potential successor, Lawrence Summers, chime in with opinions from places like Davos and from book tours.

If the U.S. economy somehow gets out of this mess without a recession and with inflation under control, Mr. Bernanke will be a hero regardless of what market critics say now. Wall Street might give his policies a chance before writing him off.

Monday, January 28, 2008

World's biggest-ever trading loss by someone not even considered a trader

The Loss Where No One Looked

Cost Société Générale

Jérôme Kerviel, the Société Générale employee who sparked the world's biggest-ever trading loss, was so low on the bank's totem pole that some didn't consider him a trader at all.

That may have been what allowed him to pull it off.

According to preliminary inquiries into the trading fraud that cost Société Générale €4.9 billion ($7.2 billion), Mr. Kerviel allegedly placed hundreds of thousands of unhedged real trades on stock-index futures markets. (Read the bank's statement1.)

For months, Mr. Kerviel avoided detection because -- even as he allegedly built up massive positions -- he always managed to square his books as a low-level trader in the "Delta One" desk: never make a big profit or loss. When one trade caught the attention of a supervisor last week, and the system collapsed, myriad small losses compounded into a huge financial hole for the bank.

A prosecutor is due to decide today whether to put Mr. Kerviel, who was questioned by police this weekend, under formal investigation. Through his attorneys, Mr. Kerviel has denied wrongdoing.

Had Mr. Kerviel been one of the A-league traders in Société Générale's most prestigious perch -- the desks that handle complex equity derivatives -- his actions likely would have drawn more attention.

To run that section of its business, Société Générale spends a fortune luring talent from France's elite engineering schools to nab people who can develop "exotic" derivative products, using sophisticated computer models.

But the Delta One desk on the seventh floor of the bank's headquarters in western Paris deals with the boring corner of the equities derivatives market: It's a low-risk division where Société Générale and its clients can place basic bets on whether a stock market index will rise or fall. Profits are generated through the sheer volume of transactions.

"We all lived in fear that something within the exotic products would blow up in our face. It never came to our mind that we might have a problem with Delta One," said a top Société Générale official.

Arrival at Delta One

Though even within Société Générale, traders held little regard for the Delta One desk, for Mr. Kerviel, just getting there had been an achievement. For his first five years at the bank, beginning in 2000, he toiled away at a back office of the prestigious equity-derivatives desk, a place that other traders derisively refer to as "the mine."

In 2005, Mr. Kerviel was promoted to the Delta One desk. There, his job was to invest in portfolios that took opposite bets on the direction of the markets. The bets essentially were supposed to offset each other in what is typically a low-risk way to make a small profit.

Mr. Kerviel was given an annual target: earn between €10 million and €15 million for the bank. And he was given a small margin to play with: the net value of his almost perfectly balanced portfolio of bets should be kept roughly under €500,000.

![[The Loss Where No One Looked]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/MI-AO846_Howdun_20080127203211.gif)

But while there, Mr. Kerviel found a way to rack up a potential liability of €50 billion via a simple scheme: Making bold trades in one portfolio and then covering up those positions with a fictitious, second portfolio. That led to a neutral trading account that wouldn't draw attention.

Scattered Trades

In addition, the trades were scattered on several separate balance sheets, and drawn into the massive flow of daily transactions, so the bank never realized Mr. Kerviel was vastly exceeding his risk limit.

The fake trades in the second portfolio were fake trades with actual banks or clients. Rather than betting on futures with an exchange -- a move that would trigger money flow and would have left trails -- Mr. Kerviel used forward transactions, which often don't require actual cash to exchange hands.

With this type of over-the-counter transaction, clients didn't know that they had been used to make a fake trade.

Books Check Out

When the bank checked Mr. Kerviel's books, the real and fictitious trades balanced out within the trader's risk limit and everything looked normal.

Several times, Mr. Kerviel's supervisors spotted mistakes in the trader's books. But Mr. Kerviel would claim it was a mistake and fix it, said Jean-Pierre Mustier, head of Société Générale's investment-banking arm.

"Société Générale got caught just like someone who would have installed a highly sophisticated alarm ... and gets robbed because he forgot to shut the window," said the Société Générale manager.

Much of Mr. Kerviel's real trading was in making bets on the future prices of big European indexes, including the Dow Jones Euro Stoxx 50, the DAX index in Germany and the CAC-40 in France.

Total Exposure

As of Jan. 18 -- the day Mr. Kerviel's ruse went astray -- Société Générale had €18 billion of exposure to the DAX, €30 billion exposure to the DJ Euro Stoxx 50 and €2 billion to the FTSE 100 Index in London, according to Mr. Mustier. All of these exposures were established this year in a short period of time, he said.

As he traded, Mr. Kerviel had to circumvent rules on how much one portfolio gain or loss could exceed a mirroring set of trades. For example, if Mr. Kerviel hypothetically bet that an index would rise in value €10, he would need to make a counter trade to cover that amount.

To balance the books, Mr. Kerviel began using the fake trades in a second portfolio, bank officials say.

For example, in his real trade, Mr. Kerviel was betting that indexes would rise at a certain point in the future. To offset that real risk, Mr. Kerviel made fake trades to show he had taken positions for a drop in the indexes, bank officials say. He forged trade documents on these trades, they add.

Covering Tracks

Once Mr. Kerviel had offset his real trading positions with fake ones, he still needed to cover his tracks. So he would erase his fake trades just before his books were checked, bank officials say. Once the threat had passed, he quickly would re-enter the trades to balance his positions. The temporary imbalance, apparent for just a few minutes, failed to set off alarms.

Mr. Kerviel also had to cancel the fake trades before confirmations of those trades were sent to the alleged counterparties such as banks. Bank officials say he used computer access codes to enter the bank's system and cancel the trades. He then created more fake trades to keep his books balanced. Mr. Kerviel's trading in 2007 essentially was flat in terms of profits and losses. But his 2008 trading yielded actual losses and trades.

The juggling act ended Friday, Jan. 18 when a counterparty trade exceeded a certain financial threshold. That then led to the discovery of a suspicious trade confirmation email.

At 10 p.m. that Friday, Mr. Mustier received a phone call that something had gone wrong.

Saturday, January 26, 2008

What Does the Fed Really Know?

I believe the monoline insurance companies like Ambac and MBIA are in worse shape than most realize, the counter-party risk in the $45 trillion Credit Default Swap market is much worse than we realize, and the exposure by various banks to their problems is much larger than currently understood. The Fed understands this, and realizes that they have been behind the curve but need to catch up. Let's go back and look at this quote from my letter just last week:"If you are a bank or regulated entity, and you have mortgage-backed securities that have been written by a AAA monocline company, you can carry that debt on your books as AAA. But as the companies get downgraded, you have to write down the potential loss. Quoting from a recent note from Michael Lewitt:" 'MBIA's total exposure to bonds backed by mortgages and CDOs was disclosed to be $30.6 billion, including $8.14 billion of holdings of CDO-squareds (CDOs that own other CDOs, or mortgages piled on top of mortgages, or, to quote Jeff Goldblum's character in Jurassic Park again, 'a big pile of s&*^'). MBIA was being priced as a weak CCC-rated credit when it issued its bonds last week; it is now being priced for a bankruptcy. MBIA's stock, which traded just under $68 per share last October, dropped another $3.50 this morning to under $10.00 per share." 'The bond insurers' business model is irreparably broken. In HCM's view, it will be all but impossible for these companies to raise capital at economic levels for the foreseeable future and certainly in enough time to work out of their current difficulties. The performance of MBIA's 14 percent bond issue will prove to have been the death knell for this business. The market needs to come to the realization that the so-called insurance that these companies were offering is not going to be there if it is needed. The fact that these companies were rated AAA in the first place will remain one of the great puzzles of modern finance for years to come.'"You can bet that the $8 billion in CDO-squareds is gone. It is a matter of time. MBIA's market cap is about $1 billion [it is now at $1.74]. Current shareholders will be lucky if they only get diluted 75%."Think this through. MBIA is still rated AAA. Ratings downgrades are just a matter of time. Banks that raised $72 billion to shore up capital depleted by subprime-related losses may require another $143 billion should credit rating firms downgrade bond insurers, according to analysts at Barclays Capital.Banks will need at least $22 billion if bonds covered by insurers, led by MBIA Inc. and Ambac Assurance Corp., are cut one level from AAA, and six times more than that for downgrades by four steps to A, as Paul Fenner-Leitao wrote in a Barclays report published today. Barclays' estimates are based on banks holding as much as 75% of the $820 billion of structured securities guaranteed by bond insurers. (Source: Bloomberg)The stocks of MBIA and Ambac have risen on speculation of take-overs or a rescue. But MBIA is going to have to cover that $8 billion of CDO squareds. With what cash? MBIA makes about $5 billion a year. It will take almost two years' earnings just to deal with the losses from CDO squareds. Not to mention the subprime mortgage exposure.But what if the above-mentioned monolines are downgraded to junk, as was ACA when it could not raise capital? As the downgrades on various mortgage assets and the CDOs continue to increase, the ability of the monolines to deal with the problems is going to come under increasing question. The losses at major banks could be much worse than $122 billion if they are downgraded to the same junk level that ACA was.And that is just the credit default swaps (CDSs) from the monolines. What about the trillions that are guaranteed by banks and hedge funds? There are a total of $45 trillion CDSs outstanding.No one is really sure who owes what and to whom, and what is the risk that there may be no one to pay that CDS when it comes due? The entire mess is going to have to be unwound in the coming quarters. It may take a year or more.I think the concern that there is the potential for a much worse credit crisis than we are currently experiencing is what is driving the Fed. They are looking at the problem from the inside, and realize that they simply have to engineer a much steeper yield curve to allow the banks to make enough profits so that they might be able to grow their way out of the crisis over time.If I am wrong and the Fed was responding to the stock market, then we will likely not see a cut this next week. But if we get another 50-basis-point cut, as I think we will, then it means the Fed is responding to concerns about the credit crisis. And we will get another cut the next meeting and the next until we get down to 2% or below.A 50-basis-point cut takes the rate to 3%. It they had cut the rate by 1.25% next week, the market would have collapsed. Better to do it in two leaps is what I think they are thinking. We will see. And it is not just the Fed that is concerned.

Tuesday, January 22, 2008

Paying for "Goldman Envy"

Paying for 'Goldman Envy'

Is Costly for Some Rivals;

Beware Chimps on Steroids

Why did some banks and brokerage firms get so badly scorched by the subprime debacle and others come through relatively untouched? What's the difference between Citigroup and J.P. Morgan Chase? Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs? UBS and Deutsche Bank? Merrill Lynch and Lehman Brothers?

On the face of things, these companies may look quite similar to those they're paired with. But Citi, Morgan Stanley, UBS and Merrill have among them written off $65 billion so far because of the credit crisis. Meanwhile, J.P. Morgan Chase, Goldman, Deutsche and Lehman have racked up write-downs totaling around $9 billion. The average share-price performance of the first quartet was minus 36% last year. The latter group was down 5.3%.

There are several reasons for this. One is luck. But something else explains a lot of the difference. The losers were infected by what one could call Goldman envy. The winners were more immune to the malady.

![[chart]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/MI-AO746_BVIEWS_20080121215750.gif)

Goldman envy started to become a serious problem after the turn of the millennium, when that Wall Street firm started to pull away from the investment-banking pack. Its profits per employee rose sharply as it deployed more of its own capital to big and sometimes complex bets -- whether it was trading securities on its own account or investing in private equity.

Of course, it wasn't just Goldman that had competitors turning green. They also were agog over the burgeoning hedge funds and private-equity groups that have been raking it in over the past few years and making ordinary investment bankers seem like poor relations. And many yearned for the juicy returns of Lehman Brothers' mortgage business.

One common response among those lagging behind has been to try to emulate the alpha males of the banking world -- in particular by increasing their bets in the once-booming fixed-income market.

Former Merrill boss Stan O'Neal would frequently berate his subordinates for not delivering Goldman-like results. Morgan Stanley's ex-second-in-command Zoe Cruz was constantly using Goldman as the yardstick for her firm's performance. And Citi executives described the megabank as a growth stock until just recently, putting its businesses under pressure to show commensurate earnings growth.

The snag is that mere desire doesn't turn a chimpanzee into a gorilla. Building successful operations takes time. Part of Goldman's success comes from the fact that its risk-taking approach -- and the accompanying discipline of risk management -- derives in part from betting its employees' money.

But desire can drive reckless growth. Take Citi and Merrill. Five years ago, neither was a big player in underwriting subprime-mortgage bonds and collateralized debt obligations, or loans often tied to risky mortgages, that were repackaged into different levels of risk. But by 2006, they were at or near the top of the league tables for both markets.

The snag is that a bank is unlikely to manage things well when it's expanding rapidly and doesn't have experience. It may put the wrong people in place, not institute the right controls and implement the wrong incentive schemes.

The banks and brokers with the biggest problems seem to have made such mistakes. UBS, for example, quickly ramped up its residential-mortgage business. But not because there was any strategic value in being in that market. Rather, it decided it wanted to bulk up in the hot securitization business, and trading and underwriting residential mortgages and CDOs was the easiest part of the market to enter.

So why were others relatively immune to Goldman envy? Well, Lehman had a big, lucrative mortgage-lending and structuring business, so it didn't need to engage in a breakneck game of catch-up. Deutsche arguably also had a more ingrained risk-taking culture. Meanwhile, J.P. Morgan had more market-savvy leadership in James Dimon than, say, Citi had in Charles Prince.

All this suggests two lessons. If you are a chimp, don't try to kid yourself that you're a gorilla. And, if you see a chimp pumping itself frantically with steroids, sell its stock.

Fed's Emergency Cut: 75bps

Fed Statement on 3/4-Point Cut

Release Date: January 22, 2008

For immediate release

The Federal Open Market Committee has decided to lower its target for the federal funds rate 75 basis points to 3-1/2 percent.

The Committee took this action in view of a weakening of the economic outlook and increasing downside risks to growth. While strains in short-term funding markets have eased somewhat, broader financial market conditions have continued to deteriorate and credit has tightened further for some businesses and households. Moreover, incoming information indicates a deepening of the housing contraction as well as some softening in labor markets.

The Committee expects inflation to moderate in coming quarters, but it will be necessary to continue to monitor inflation developments carefully.

Appreciable downside risks to growth remain. The Committee will continue to assess the effects of financial and other developments on economic prospects and will act in a timely manner as needed to address those risks.

Voting for the FOMC monetary policy action were: Ben S. Bernanke, Chairman; Timothy F. Geithner, Vice Chairman; Charles L. Evans; Thomas M. Hoenig; Donald L. Kohn; Randall S. Kroszner; Eric S. Rosengren; and Kevin M. Warsh. Voting against was William Poole, who did not believe that current conditions justified policy action before the regularly scheduled meeting next week. Absent and not voting was Frederic S. Mishkin.

In a related action, the Board of Governors approved a 75-basis-point decrease in the discount rate to 4 percent. In taking this action, the Board approved the requests submitted by the Boards of Directors of the Federal Reserve Banks of Chicago and Minneapolis.

Sunday, January 20, 2008

China's Yifu Lin Named Chief Economist of World Bank

World Bank to Name Lin

New Chief EconomistThe World Bank is poised to name a scholar from China as its chief economist, a move by bank president Robert Zoellick to address criticism that the institution needs more senior management from developing nations and should be better attuned to emerging markets.

![[Robert Zoellick]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/HC-FL670_Zoelli_20051020134318.gif)

Justin Yifu Lin is expected to fill the vacancy left by François Bourguignon, who retired as chief economist in October, according to bank officials. The 55-year-old Mr. Lin is the founder and director of the China Center for Economic Research at Peking University, and has frequently served as an adviser to the Chinese government. He would be the first Chinese citizen to be the Bank's chief economist, a job that has traditionally gone to eminent academics from the U.S. or Europe.

The choice of Mr. Lin would continue a shift in the World Bank's relationship with China, which for years was a major recipient of the bank's aid. With strong government finances and $1.5 trillion in foreign-exchange reserves, China today has little need for outside financial assistance. Although the bank continues to run projects in China in areas like environmental protection, its loans to the country now carry more commercial terms. Last year, for the first time, China agreed to contribute to the World Bank's fund for aid to the poorest countries.

The chief economist can play a powerful role at the World Bank, by setting its research agenda and helping establish its intellectual direction. Under the tenures of Stanley Fischer and Lawrence Summers, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the bank forcefully advocated that poor countries liberalize their economies by repealing trade restrictions and opening their markets to foreign investment.

Under Joseph Stiglitz in the late 1990s, the bank became a critic of the International Monetary Fund's handling of financial crises, arguing that the IMF prescriptions were too fiscally restrictive and could worsen downturns.

The world's largest poverty-fighting institution since World War II, the World Bank has long been plagued by disagreements among poor countries that receive its aid and the wealthy countries that provide most of its funding. Mr. Zoellick has made efforts to bridge those gaps since he became Bank president in July.

Mr. Lin's own career over the last three decades has been founded on analyzing China's approach to economic development. He was born in Taiwan and earned a master's in business administration from National Chengchi University in Taipei in 1978, the year that mainland China began its market-opening reforms.

The next year, Mr. Lin, then serving as an officer in the Taiwanese army, left for rival China. Numerous published accounts over the years have said that Mr. Lin defected by swimming to China from the Taiwanese-controlled island of Quemoy, also called Kinmen. Mr. Lin went on to study at Peking University, China's top university. He earned a doctorate in economics from the University of Chicago in 1986, becoming one of the first students from China to complete such a degree in the U.S. during the reform era.

Mr. Lin gave a hint of how he might apply lessons from China to other developing nations in lectures at Cambridge University last year. China and Vietnam, he noted, have achieved long periods of fast economic growth while flouting some conventional free-market policies. Many countries in Eastern Europe and Latin America, by contrast, have been quicker to liberalize but have worse records of sustaining growth and reducing poverty.

Yet Mr. Lin didn't argue that China's specific policies would necessarily work elsewhere. He argued more for experimentation and gradualism than adopting a formula. "Principles or experiences of other countries should not be applied in a dogmatic way," Mr. Lin said then, according to a copy of his lecture notes. "A gradual, piecemeal approach to reform and transition could enable the country to achieve stability and dynamic growth simultaneously and allow the country to complete its transition to a market economy."

Mr. Lin couldn't be reached for comment in Beijing over the weekend. The Bank's governing board hasn't yet approved his appointment, but final approval is expected by the end of the month.

Talk Strong Dollar Won't Make Dollar Strong

Markets and the Dollar

By DAVID MALPASSHigh-profile foreign investments in U.S. financial institutions have been making headlines recently. But those capital injections are a trickle when compared to the outward flood of dollars from U.S. companies seeking to increase assets and earnings in some currency other than the sinking dollar.

To fight financial market turbulence and a slowing economy, the Fed has injected extra liquidity, cut the discount rate, and cut the fed funds rate a full percent. As it prepares to hit the rate-cut panic button harder, the Fed should also try using its most powerful tool, a stronger dollar, to draw liquidity into credit markets, reduce oil prices and restart economic growth.

At 4.25%, the fed funds rate is now below both the 4.3% consumer price inflation rate and the 4.9% third-quarter real growth rate. That's a more proactive interest rate stance than any previous pre-recession environment. The Fed is trying to make the best of a bad monetary situation. Most of the damage was done once the fed-funds rate was forced down to 1% in 2003 and held artificially low as the value of the dollar evaporated and housing bubbled through 2005.

The Fed's late-December policy innovation -- auctioning funds through the discount window -- will gradually shift as much as 7% of the Fed's $900 billion in assets from Treasury bills to collateralized bank loans. This is constructive medicine. It should help deposit-taking banks finance mortgages, and also leave sought-after Treasury bills in the market.

While some worry that central banks are losing their power due to the size and complexity of global markets, the more likely problem is too much power. Central banks cause wide swings in interest rates and the value of their currencies. With a delay, the swings penetrate the price level as inflation and deflation. Central banks are the only institutions that have a literally unlimited balance sheet -- in the case of the Fed, the ability to instantaneously create and inject into the economy as many billions of dollars as it determines useful (by buying Treasury bills or acquiring temporary control of mortgage-related securities).

The elephant in the living room -- the topic Washington won't broach -- is the dollar itself as a powerful but unused monetary policy tool. The Fed didn't mention the dollar in its Dec. 11 rate-decision communiqué, nor in its November economic forecasts. In his recent 500-page memoir, and his Dec. 13 opinion piece on this page, former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan barely mentions the wide swings in the value of the dollar -- probably the most important economic and investing variable in the last decade -- and their causal connection to first deflation and now inflation.

President Bush showed no embarrassment over dollar weakness in a November interview with Fox Business News. He was asked: "Even if the economy is weak, shouldn't the dollar be strong?" Rather than a simple "yes," the president said: "All I can tell you is the policy of this government is a strong dollar. We believe the marketplace is the best place to set the exchange rates." Pressed if he was satisfied with where the exchange rates are now, he replied: "Well, I am satisfied with the fact that we have a strong-dollar policy and know that the market ought to be setting the exchange rate between the U.S. dollar and other currencies."

Current U.S. dollar policy leaves only "the market" responsible for the dollar's collapse. Not known for deep thinking, the currency markets tend to sell currencies issued by countries which make markets responsible for currency values. The euro found this out the hard way in 2000 when Wim Duisenberg, then head of the European Central Bank, invited markets to set the value of the euro based on Europe's economic fundamentals. Look out below. The free fall didn't stop until Jean-Claude Trichet took over and installed policies to preserve the euro's value regardless of the market's view of economic fundamentals.

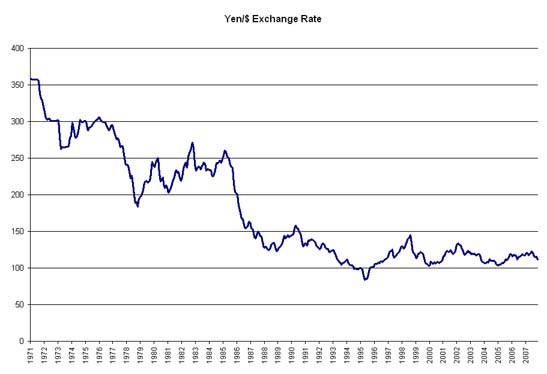

There's no reason to think markets set currency values based on economic fundamentals anyway. In the early 1990s, Japan's yen was super-strong through 1995 even though it pushed Japan into a decade-long deflation spiral. Currency markets are famous for going to extremes, distorting economies and people's lives without any qualm of conscience or reference to value.

One of the Fed's main explanations for its hope that inflation could moderate despite dollar weakness -- the same explanation it used in the late 1990s for claiming that dollar strength wouldn't cause deflation -- is its research showing that the "trade-weighted" value of the dollar is not well-correlated to U.S. inflation. The obvious problem with this approach is that the trade-weighted dollar mixes together changes in the dollar's value with changes in the value of foreign currencies.

The dollar's trade-weighted value can be down due to foreign currency appreciation, and vice versa, with little impact on U.S. inflation. In contrast, the connection between gold-measured changes in the value of the dollar and the U.S. inflation rate is too clear to keep ignoring.

The relationship between currency values and inflation or deflation is equally strong in other countries. China is suffering high inflation now because the gold-measured value of the yuan is weak (even though the trade-weighted yuan is strong due to dollar and yen weakness). Yen strength in the late 1980s and early '90s drove Japan into a deflation spiral, the same process that struck the U.S. in the late '90s.

By saying they want a stronger dollar, the Fed, the president or the Treasury could make it happen. Government policy makers have almost absolute control over perceptions of the future scarcity of dollars. This controls the demand for dollars almost as much as it does the supply, setting its value as much or more than rates do.

* * *

But world markets expect a dovish Fed now and in the future. This is driving capital away from the dollar. Washington can easily change this perception by linking a stronger dollar to its much-needed fight against inflation. Coordinated currency interventions are a helpful and decisive signal of a monetary policy change, but aren't required.

As a next step in addressing financial-market turbulence, the Fed and the administration should say they want the dollar to strengthen in order to attract capital, spur U.S. growth and slow the inflation rate. There's still time. Jobless claims are not yet at recession levels, stock prices are high, and exports are booming. The weak dollar doesn't seem to be at a tipping point -- it's more of a constant drag on the economy, like American litigiousness and the anti-growth tax code.

But the harder the economy works to repair the weak-dollar damage from the bottomless liquidity punch bowl of 2004, the deeper the urge for the "hair of the dog" medicine of more rate cuts. Those may weaken the dollar more, adding to inflation. The clear alternative is to strengthen the dollar first.

Mr. Malpass is chief economist at Bear Stearns.

Friday, January 18, 2008

China's real estate shows sign of cooling

WSJ, January 18, 2008

HONG KONG -- Early signs of a softening real-estate market in southern China's two largest cities suggest that government measures to temper investors' zeal for property could be working.

Discounts touted by developers to drum up transactions and a decline in new-home prices reflect concerns that the market has risen too high too fast. They have also left investors wondering whether weakness in China's south might foreshadow the first nationwide downturn in housing prices since private homeownership became a reality in China in the late 1990s.

Prices for new homes in Shenzhen, a southern boomtown of nine million that borders Hong Kong, dropped 8% from September to the end of the year, according to global real-estate advisers DTZ. In nearby Guangzhou -- China's third-largest city, behind Beijing and Shanghai, and the nexus of its manufacturing might -- prices for new homes fell 9.9% in November from a high of 11,574 yuan ($1,600) a square meter in October, according to city-government statistics. The declines come after years of consistently strong market sentiment in both cities.

![[Cooling Market chart]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/AI-AM827_CPROPE_20080117163614.gif)

A sharper or broader property downturn in China could shake investor confidence, further pressure stocks and hurt the booming economy. But for now, the situation stands in contrast to the housing picture in the U.S. There, a broad decline in prices is linked to fears of recession, and the government is trying to spur activity, not damp it.

"Because inflation is higher, [Chinese] policy makers are increasing their resolve" to curb lending, says Mei Jianping, a professor of finance and a real-estate specialist at the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business in Beijing. "Some cities will adjust more than others, but this is going to be a nationwide phenomenon."

Many brokers and analysts are reluctant to draw too many conclusions from the downturn in the south. They point to the swelling tides of Chinese that continue to pour into the big cities, looking to buy a first home.

"Fundamental demand in China across the board is very strong and will remain that way for the next 10 years," says Alan Chiang, the Shenzhen-based head of mainland China residential property at real-estate broker DTZ. "We still have a very, very long road to go on urbanization."

China's property prices have reached dizzying highs in recent years, as the nation's cities have taken in tens of millions of new residents and the number of middle-class homeowners rises. Investors have followed the property boom with speculative money.

![[Guangzhou]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/AI-AM833_CPROPE_20080117162919.jpg) |

| Prices for new homes in Guangzhou fell 9.9% in November from October. |

After posting double-digit growth for several years, real-estate markets in Shenzhen began to wobble this past summer as central authorities rolled out their latest measures to curb speculation there. First, transaction volumes plunged, with November levels falling 81% from a high of 8.6 million square feet in January 2007, according to DTZ. The decline in new-home prices followed.

On the ground, the declines have sparked a phenomenon so far unseen in these cities: promotional gimmicks by developers that, for instance, had residents of Guangzhou lining up overnight for a small discount or free furniture thrown in with a purchase. Chinese news media have seized on any sign of trouble, with readers keenly tuned to the topic. One report this month said Shenzhen-based real-estate broker Chuanghui was shutting hundreds of branches because of declining interest from home buyers.

Central-government policy makers have pressed on with their campaign to curb access to easy credit. This past week, the government again increased the ratio of capital that banks must hold in reserve, a measure it used 10 times last year to restrain bank lending.

Todd Schubert, an analyst at Deutsche Bank AG, says the slowdown is evidence that Beijing's antispeculative measures are taking root. Mr. Schubert expects further price declines across the country in 2008.

![[Shenzhen]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/AI-AM832_CPROPE_20080117162917.jpg) |

| In Shenzhen, prices dropped 8% from September to the end of the year, according to global real estate advisers DTZ. |

Such a decline could have wider implications for investors in the stock market, since stock prices and home prices are so closely linked in China's closed capital system. Ordinary Chinese investors, with few options, plow stock-market gains into real estate, and vice versa. In recent years, that cycle has spurred both markets to records; now, as stocks retreat, the cycle could work in reverse. The measures are also likely to put a crimp in China's high-flying property developers.

"What the government is trying to do is shift that wealth from the private developers to the general public," says Eric Lam, general manager for the Guangzhou office of Colliers International, a property broker and consultant.

In the big picture, though, the declines don't necessarily spell widespread trouble for a country that has seen a benchmark index of property prices in 70 major cities rise at a solid rate in December, compared with last year. The latest figures, released Thursday by Beijing, showed price growth holding steady in general across the country.

do some research before attacking Ben

Tuesday, January 15, 2008

Dollar Recycling, New Style

Friday, January 11, 2008

Chinese, Saudi to Invest in Citibank

Alwaleed, China to Invest in Citi

Prince Alwaleed bin Talal is poised to once again come to the rescue of Citigroup Inc.

This time, the Saudi billionaire is expected to be joined by other investors, including the China Development Bank, people familiar with the matter said. While it isn't clear how much Prince Alwaleed will invest, the Chinese entity is expected to invest roughly $2 billion, one person said. Prince Alwaleed's total stake in Citigroup is likely to remain below 5% in order to avoid regulatory scrutiny. However, given that Citi has a stock market value of $140 billion, even a 1% stake would end up being a significant sum of money, and a potential vote of confidence in the struggling bank.

While Citigroup is still working out details of the planned investments, and there's a chance they could fall apart, the bank is hoping to collect a total of $8 billion to $10 billion from a number of investors, likely including at least one fund affiliated with a foreign government, the people said.

China Development Bank was set up in 1994 as one of the country's three policy banks. On Dec. 31, China's sovereign wealth fund China Investment Corp. made an infusion of $20 billion into the bank, in an move to turn the bank into a commercial lender.

This would be at least the third major investment by a Chinese institution in a struggling Wall Street firm. China Investment Corp. is investing $5 billion in Morgan Stanley, while Citic Securities agreed to a $1 billion investment in Bear Stearns Cos., though Bear will also invest that amount in the Chinese firm, albeit over many years.

Citi is also talking to other existing shareholders, including U.S. investment funds, to potentially up their stake in the bank.

A cash infusion would leave Prince Alwaleed in a familiar role. In 1991, he pumped $590 million into what was then known as Citicorp. The investment, which was in the form of a private placement of convertible preferred stock, gave him an ownership stake of nearly 15% at the time. For years, he was Citi's largest individual shareholder.

Prince Alwaleed ceded that title last month, when Abu Dhabi's investment arm paid $7.5 billion for a 4.9% stake in the cash-strapped company.

In recent weeks, though, the bank's troubles have continued to pile up. Citigroup decided to bring onto its balance sheet $49 billion in assets from seven struggling investment affiliates, a move that further depleted its already weak capital ratios. The New York conglomerate also is facing more than $15 billion in fourth-quarter losses stemming from its exposure to mortgage-related investment vehicles.

Citigroup is hoping to unveil the investments Tuesday when it reports fourth-quarter earnings. At the same time, the company also could announce that it is cutting its dividend payment.

Thanks to his large stake, Prince Alwaleed has wielded considerable influence at Citigroup. In 2006, he publicly warned Citigroup's then-chief executive, Charles Prince, that he needed to take "Draconian" steps to contain the company's spiraling expenses. Months later, Mr. Prince followed up with a cost-cutting plan that included the elimination of 17,000 jobs, or about 5% of Citigroup's workforce.

Despite Citigroup's struggles through the first three quarters of last year, Prince Alwaleed continued to publicly support Mr. Prince. But last fall, as Citigroup executives realized they were facing billions of dollars in write-downs, Prince Alwaleed withdrew that backing. In early November, Mr. Prince handed in his resignation.

Wednesday, January 09, 2008

Top 10 recommendations for 2008

My thumbs up for their 4, 5, 9. I am a little iffy on 2. I disagree with them on 'remain heavily underweight banks', and I think banks should be an overweight from mid of 2008, or even a bit earlier. On their last point, stagflation, I have yet to see the real evidence. Others I am not sure.

You're welcome to share your thoughts on the list.

1.Remain heavily underweight banks, particularly investment banks that have displayed monumental stupidity. Do not assume that a change at the top will automatically convert them into temples of wisdom (unless it is accompanied by demands for the departing to repay bonuses based on bets that turned out disastrously). Better to assume that, like subprime-based DOs, there are layers of rot that can make the entire product dangerous to your financial health.

2.Remain overweight Emerging Markets, emphasizing those that are oil, gas, and/or food exporters.

3.Soaring food costs threaten stability for some Third World economies. We have been ardently endorsing India since we returned from our leave of absence a year ago. We are now more cautious, because a weak monsoon could be politically and economically destabilizing at a time of $4 corn and $10 wheat.

4.Remain heavily overweight gold - both stocks and the ETF. Gold is almost as good a protection against banking problems as SKF - the UltraShort Financials ETF - a security which may not be a suitable investment in some portfolios.

5.We continue to believe that the Agricultural stocks are the pre-eminent investment class of our time. Farm incomes are rising rapidly and, in the US, farms and farm land are the real estate assets that are rising in value and are virtually immune to foreclosures. That means the leading Ag companies have great pricing power and minimal credit problems. We now hear suggestions that because food inflation has finally made it to the cover of The Economist, it is time to start moving toward the exits. Not so: We think that fine cover story could be the atonement - At Last! - for the magazine's famous 1999 cover: $5 Oil.

6.Remain overweight oil and gas producers, including the Alberta oil sands producing companies. As disappointed as we are with the new royalty schemes in that province, Alberta certainly remains more attractive than Nigeria or Angola - and much more attractive than Russia, Kazakhstan or Venezuela.

7.We think it is time to begin accumulating the refiners that are equipped to handle heavy high-sulfur crude. The collapse of the crack spread has savaged refiners' earnings, but that will eventually rebound. The Saudis have virtually turned out the Light, and less and less of the oil that the Gulf states will be lifting will be of the most desirable grades.

8.Retain the base metal stocks that have long-life unhedged reserves in secure areas. Even if there is a global recession caused by global collapses of subprime paper and LBO loans, it will not be deep enough to drive base metal prices back to 2004 levels - but would be worrisome enough to push further mine development even farther into the future.

9.When borrowing, borrow where possible in dollars. When investing, invest where possible in other currencies.

10.Stagflation is a bad backdrop for bonds - and for non-commodity stocks. The central bankers could have headed it off had Wall Street behaved with a modicum of morality, but the Fed and its brethren are forced into sustained reflation because of the global solvency crisis. Corporate earnings for most sectors will not meet current optimistic Street forecasts, and rising inflation will reduce the market's P/E.

Saturday, January 05, 2008

Decoupling or recoupling?

An old Chinese myth

Contrary to popular wisdom, China's rapid growth is not hugely dependent on exports

MOST people suppose that China's economic success depends on exporting cheap goods to the rich world. If so, its growth would be seriously dented by a stuttering American economy. Headline figures show that China's exports surged from 20% of GDP in 2001 to almost 40% in 2007, which seems to suggest not only that exports are the main driver of growth, but also that China's economy would be hit much harder by an American downturn than it was during the previous recession in 2001. If exports are measured correctly, however, they account for a surprisingly modest share of China's economic growth.

The headline ratio of exports to GDP is very misleading. It compares apples and oranges: exports are measured as gross revenue while GDP is measured in value-added terms. Jonathan Anderson, an economist at UBS, a bank, has tried to estimate exports in value-added terms by stripping out imported components, and then converting the remaining domestic content into value-added terms by subtracting inputs purchased from other domestic sectors. At first glance, that second step seems odd: surely the materials which exporters buy from the rest of the economy should be included in any assessment of the importance of exports? But if purchases of domestic inputs were left in for exporters, the same thing would need to be done for all other sectors. That would make the denominator for the export ratio much bigger than GDP.

Once these adjustments are made, Mr Anderson reckons that the "true" export share is just under 10% of GDP. That makes China slightly more exposed to exports than Japan, but nowhere near as export-led as Taiwan or Singapore (which on January 2nd reported an unexpected contraction in GDP in the fourth quarter of 2007, thanks in part to weakness in export markets). Indeed, China's economic performance during the global IT slump in 2001 showed that a collapse in exports is not the end of the world. The annual rate of growth in its exports fell by a massive 35 percentage points from peak to trough during 2000-01, yet China's overall GDP growth slowed by less than one percentage point. Employment figures also confirm that exports' share of the economy is relatively small. Surveys suggest that one-third of manufacturing workers are in export-oriented sectors, which is equivalent to only 6% of the total workforce.

Even if the true export share of GDP is smaller than generally believed, surely the dramatic increase in China's exports implies that they are contributing a rising share of GDP growth? Mr Anderson's work again counsels caution. Although the headline exports-to-GDP ratio has almost doubled since 2000, the value-added share of exports in GDP has been surprisingly stable over the same period (see left-hand chart). This is explained by China's shift from exports with a high domestic content, such as toys, to new export sectors that use more imported components. Electronic products accounted for 42% of total manufactured exports in 2006, for example, up from 18% in 1995. But the domestic content of electronics is only a third to a half that of traditional light-manufacturing sectors. So in value-added terms exports have risen by far less than gross export revenues have.

Many of China's foreign critics remain sceptical. They argue that China's massive current-account surplus (estimated at 11% of GDP in 2007) proves that it produces far more than it consumes and relies on foreign demand to buy the excess. In the six years to 2004, net exports (ie, exports minus imports) accounted for only 5% of China's GDP growth; 95% came from domestic demand. But since 2005, net exports have contributed more than 20% of growth (see right-hand chart).

This is due not to faster export growth, however, but to a sharp slowdown in imports. And even if the contribution from net exports fell to zero, China's GDP growth would still be close to 9% thanks to strong domestic demand. The boost from net exports is in any case unlikely to vanish, even if America does sink into recession, because exports to other emerging economies, where demand is more robust, are bigger than those to America. According to Standard Chartered Bank, Asia and the Middle East accounted for more than 40% of China's export growth in the first ten months of 2007, North America for less than 10%.

Multiplier effects

China's economy is driven not by exports but by investment, which accounts for over 40% of GDP. This raises an additional concern: that weaker exports could lead to a sharp drop in investment because exporters would need to add less capacity. But Arthur Kroeber at Dragonomics, a Beijing-based research firm, argues that investment is not as closely tied to exports as is often assumed: over half of all investment is in infrastructure and property. Mr Kroeber estimates that only 7% of total investment is directly linked to export production. Adding in the capital spending of local firms that produce inputs sold to exporters, he reckons that a still-modest 14% of investment is dependent on exports. Total investment is unlikely to collapse while investment in infrastructure and residential construction remains firm.

An American downturn will cause China's economy to slow. But the likely impact is hugely exaggerated by the headline figures of exports as a share of GDP. Dragonomics forecasts that in 2008 the contribution of net exports to China's growth will shrink by half. If the impact on investment is also included, GDP growth will slow to about 10% from 11.5% in 2007. This is hardly catastrophic. Indeed, given Beijing's worries about the economy overheating, it would be welcome.

The American government frequently accuses China of relying excessively on exports. But David Carbon, an economist at DBS, a Singaporean bank, suggests that America is starting to look like the pot that called the kettle black. In the year to September, net exports accounted for more than 30% of America's total GDP growth in 2007. Another popular belief looks ripe for reappraisal: it seems that domestic demand is a bigger driver of China's growth than it is of America's.

Friday, January 04, 2008

Mutual Fund Oscars

Morningstar Singles Out

Fidelity's Danoff on Stocks,

Pimco's Gross on BondsTwo well-known mutual-fund managers who steered clear of the subprime-loan downturn in 2007 and delivered impressive returns to stock and bond investors received honors yesterday from investment researcher Morningstar Inc.

Will Danoff, of Fidelity Contrafund, one of the country's biggest mutual funds, and the smaller Fidelity Advisor New Insights Fund, was named Morningstar Domestic Stock Fund Manager of the Year.

![[Will Danoff]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/HC-CP664_Danoff_20051031180419.gif)

Meanwhile, Morningstar's Fixed-Income Manager of the Year went to Pacific Investment Management Co.'s Bill Gross. His team running Pimco Total Return and Harbor Bond Fund has won the award three times. Pimco is a unit of Allianz SE.

Separately, Hakan Castegren, lead manager at Harbor International Fund, was selected International Stock Manager of the Year, an award he won also in 1996. The foreign large-cap value fund returned 21.8% in 2007, topping 96% of its class, Morningstar said.

Mr. Danoff led the $80.8 billion Contrafund to a 19.8% gain in 2007, topping its large-cap growth category average by more than six percentage points, according to Morningstar.

Technology stocks worked especially well in 2007 for the fund, which is closed to new investors. Mr. Danoff pointed to top performers including Research In Motion Ltd, Google Inc. and Apple Inc.

"Avoiding financials was a big win, as well," Mr. Danoff said. "When I saw many of the issues financials were wading through, I stepped back."

If markets decline in 2008, he adds, Contrafund's team will likely use it as an opportunity for long-term-minded shareholders to buy into companies with strong fundamentals and top management.

![[William Gross]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/HC-GK507_Gross_20070823220030.gif)

Mr. Danoff says another key performer in 2007 was the fund's investment in energy and materials sectors. "Those turned out to be very good this year, and that really helped the fund's returns," he added. "And with decent demand coming out of emerging markets, prices continue to be strong."

Morningstar gives awards to managers each January based on strong investment performance in the previous calendar year, superior long-term results, and a proven commitment to investors in their funds.

"All of this year's winners made real money for investors this year as well as over longer periods," said Christine Benz, director of mutual-fund analysis at Morningstar. "These are all very consistent performers."

She noted that Mr. Danoff's Contrafund dropped 10% in 2002 versus the broader market's 22.1% loss. During the past 10 years, the fund's average annualized return of 10.7% tops 96% of its large-cap growth rivals, Ms. Benz added.

"It was a $30 billion in assets-under-management fund," Ms. Benz said. "Danoff's record has built quite a following over the years."

Morningstar emphasized that its international award in 2007 went to the team Castegren leads, which includes analysts at asset manager from Boston-based Northern Cross International Investment Management.

"The team has shown a lot of patience in looking for bargain stocks," Ms. Benz said. "He's very long-term focused and has been on the fund for 20 years. This is another large fund, with $27.2 billion in assets and very stable management."

Meanwhile, Mr. Gross is one of the most-respected bond-fund managers in the business, she added. "He's our only three-time winner," Ms. Benz said. "He's a manager who isn't afraid to take bold stances when he and his team thinks it will profit investors over the long term."

For example, in 2006, long before anyone else was worried about a downturn in housing, Mr. Gross moved to shield his portfolios from a downturn, Ms. Benz said. "At first, that led the fund to look out of step with its intermediate bond-fund peers," she added.

Still, Pimco Total Return was able to put up results close to the category's average. "But that was relatively weak for such a strong long-term performer," Ms. Benz said. "It's not typically an average, run-of-the-mill type of bond fund."

In 2007, bets by Mr. Gross and his team paid off. In the year, it posted a preliminary 9.1% total return versus 4.7% for its peer group.

In addition to this year's bond-fund manager of year award, Mr. Gross won for the same category in 1998 and 2000.

"It has been an honor and a real team effort in each of those years, especially in 2007," Mr. Gross said. "Our success came from avoiding the subprime debacle and taking advantage of the policy moves, namely the Fed cuts, that emanated from it."

Thursday, January 03, 2008

China's SWF Act Again

China Taps Its Cash Hoard To Beef Up Another Bank

Source: WSJAn injection of $20 billion by China's sovereign-wealth fund into policy lender China Development Bank is the latest example of how the country is using its surplus of cash to beef up the balance sheets of local banks.

The newly formed fund, China Investment Corp., or CIC, has attracted much attention overseas for its high-profile purchase of stakes in U.S. private-equity firm Blackstone Group LP and, two weeks ago, Wall Street firm Morgan Stanley. But the fund, formed from $200 billion of foreign-exchange reserves, has set aside as much money for recapitalizing domestic financial institutions as for overseas investment.

China Development Bank, known as CDB, has also cut a global profile recently. Earlier in 2007, it invested $3 billion in Barclays PLC to help support the British bank's ultimately unsuccessful bid for ABN Amro Holding NV. It has specialized in lending to domestic infrastructure projects and has been a pioneer in developing China's nascent bond markets.

![[Balancing Act chart]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/AI-AM550_CDB_20080101161246.gif)

Plans for the capital injection into CDB had been in the works since at least last January. Beijing had already dipped into its bulging foreign-exchange reserves, now topping $1.4 trillion, to shore up the books of the country's three biggest listed banks ahead of their initial public offerings. Capital injections into those banks from Central Huijin Investment Co., a government agency that has been incorporated into CIC, totaled about $60 billion.

Now those formerly insolvent state-owned lenders, led by Industrial & Commercial Bank of China Ltd., rank among the world's biggest banks. They have begun to use the massive sums raised by their initial public offerings to expand globally.

Next in line for a huge pre-IPO infusion will be Agricultural Bank of China. CIC is expected to inject about $45 billion to rehabilitate the sprawling state bank and prepare it for an IPO.

China's central bank announced the CDB capital injection in a statement posted Monday on its Web site, saying the infusion will "increase China Development Bank's capital-adequacy ratio, strengthen its ability to prevent risk, and help its bank move toward completely commercialized operations." The move appears timed to ensure CDB can count the fresh capital on its 2007 books.

Formed in 1994, CDB is in some ways a World Bank with Chinese characteristics. It has been molded by the leadership of Chen Yuan, a former central-bank vice governor and son of Chen Yun, who was one of the architects of China's economic overhauls. He has looked to outsiders like former U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker for advice and asked international auditors to check his bank's books. At the same time he used his bank's money to back major government initiatives like the Three Gorges Dam -- a project the World Bank decided against funding. The bank has been active in lending to Chinese projects abroad, including through a fund it set up to focus on Africa, and in supporting Chinese companies looking to expand overseas.

CDB's capital base has been pinched by continued lending growth without an increase in equity. It doesn't get its funding from deposits by China's 1.3 billion people, instead relying for most of its capital on bond sales -- which have totaled more than two trillion yuan ($274 billion) since its founding.

The bonds represent about one-fifth of the debt securities outstanding on China's financial markets. Internationally, CDB has issued more bonds than any other Chinese institution.

At the end of 2006, the bank said its capital-adequacy ratio slipped by one percentage point to just above 8%, the lowest level Chinese regulators consider safe.

As most of CDB's lending is to government agencies, or projects backed by Beijing, loan losses have tended to be low. Of the 576 billion yuan in loans it disbursed in 2006, nearly 20% went to each of three sectors: power, road and public facilities.

A CDB spokeswoman said the bank had no comment on the injection beyond the central bank's statement.