Based on the S&P 500's current multiple of 16.8 times earnings over the past 12 months, according to Thomson Reuters, investors are anticipating modest inflation. Since 1950, in periods when inflation ran between 2% and 4% (as it has through much of this decade), stocks traded at an average price/earnings ratio of 17.4, according to Strategas Research Partners. But in a 4% to 6% inflation environment, the average P/E ratio dropped to 14.7.Last Friday, the Labor Department reported that the consumer price index for May was 4.2% higher than a year earlier. If inflation rises closer to 6%, it could drive the market's P/E ratio closer to 14. Currently, earnings for the S&P 500 companies are expected to come in at about $92 a share, and a three-percentage-point contraction in P/E multiples means fair-market value for the S&P 500 index drops by 276 points.

Tuesday, June 17, 2008

Inflation and stock market

Monday, June 16, 2008

Stephen Roach: New stagflation made in Asia

First, world has never been so integrated in terms of trade:

Second, inflation in Asia is flashing red alert:The globalisation of trade flows is a new transmission mechanism of worldwide inflation that was not evident in the 1970s. According to estimates from the International Monetary Fund, overall exports should hit a record 32.5 per cent of world gross domestic product in 2008...

For developing Asia as a whole, consumer price index inflation hit 7.5 per cent in April 2008, close to a 9½-year high and more than double the 3.6 per cent pace of a year ago. Sure, a good portion of the recent acceleration in pricing is a result of food and energy – critically important components of household budgets in poorer countries and yet items that many analysts mistakenly remove to get a cleaner read on underlying inflation. But even the residual, or "core", inflation rate in developing Asia surged to 3.8 per cent in April, more than double the 1.8 per cent pace of a year ago.

China's inflation problem is much deeper than the food and energy price shocks that thus far have played a disproportionate role in driving its consumer price index higher. Also at work are serious wage pressures reflecting, in part, increases in minimum wages associated with new labour reform laws. Meanwhile the People's Bank of China has held its policy lending rate below headline inflation, resulting in negative real short-term interest rates.The result has been an ominous increase in Chinese inflationary expectations, strikingly reminiscent of similar occurrences that plagued the developed world in the 1970s and early 1980s. History does not treat kindly a serious deterioration in inflationary expectations. The longer such a trend persists, the more wrenching the monetary tightening required to arrest it – and the greater the risk of a subsequent hard landing. That is the last thing China wants or needs.China is hardly alone in its reluctance to take firm action against a worrying build-up of inflationary pressures. That is true throughout most of developing Asia, where hyper-growth is viewed as the panacea for the aspirations of a growing middle class. Throughout the region, central banks are keeping short-term interest rates far too low to combat these inflationary pressures. For developing Asia as a whole, a GDP-weighted average of policy rates is currently about 6.75 per cent, fully three-quarters of a percentage point below the 7.5 per cent headline inflation rate.

Alan Blinder on "Bubble and Central Banks"

He differentiates two types bubbles: bank-centered bubbles and bubbles not based on bank lending. Central banks have more and better information on the bank-centered bubbles and have a lot of tools to deal with it rather than raising interest rate. For the non-bank-based bubble, central banks have no information advantage and monetary policy tools rarely "fit the crime". (source: NYT)

I would argue that the central bank's proper role is fundamentally different in the two types of bubbles. Here's why:

When bubbles are not based on bank lending, the Fed has no comparative advantage over other observers in distinguishing between rising fundamentals and bubbly valuations. It may see bubbles where there are none, or fail to recognize them until it's too late — or probably both.

Indeed, at the Fed, I recall Mr. Greenspan thinking that he saw a stock market bubble as early as 1995, when Internet stocks barely existed and the Dow was under 5,000. Fortunately, he did not make the mistake of trying to burst it. Conversely, the tech bubble became obvious only in 1999 — by which time it was already enormous.

That's the first problem, and it's a huge one. Here's the second:

Once a central bank correctly recognizes a bubble's existence, what is it supposed to do? The Fed has no instruments aimed directly at, say, tech stocks, and practically no instruments aimed at stock prices more broadly. (Those who argued that higher margin requirements would have worked were engaged in deeply wishful thinking.)

Of course, the Fed could have raised interest rates. But why would raising the federal funds rate by, say, two to three percentage points have ended the stock market mania when investors were expecting 19 percent annual returns in the stock market? That much monetary tightening, however, might well have stopped the economy in its tracks. If that strikes you as a good bargain, you might enjoy reading Cotton Mather's autobiography.

But a bank-centered bubble is starkly different in both respects.

As long as the central bank is also a bank supervisor and a regulator, it is extraordinarily well placed to observe and understand bank lending practices — much better positioned than almost anyone else. Beyond merely knowing more, part of a bank supervisor's job is to make sure that banks don't engage in unsafe and unsound lending, and to scowl at or discipline them if they do. We know that America's bank regulators fell down on the job as the housing-mortgage bubble inflated. But that was a failure of bank supervision, not of monetary policy.

AND what about instruments specifically aimed at the bubble? Whereas the Fed's kit bag is pretty much empty when it comes to stock-market prices, it is stuffed full when it comes to taking aim at bank lending practices. Escalating upward from a sternly arched eyebrow to an outright prohibition of certain types of lending — for example, subprime loans with no documentation for 100 percent of a home's appraised value — bank supervisors have a broad range of finely calibrated weapons at their disposal. Like the Mikado, they can "let the punishment fit the crime."

Market is betting on rate hike soon

(source: FRED)

The odds for August rate hike has been increasing:

(source: Cleveland Fed)

Multiple rate hikes are expected:

(source: CNBC)

Why airfare becomes so expensive?

Saturday, June 14, 2008

Lehman: Independent for How Long?

Lehman: Independent for How Long?

The diversified investment bank does not have the requisite strength or size for the current environment. But suitors are holding back—for now

by Ben Levisohn

Lehman Brothers (LEH) appears to have averted a Bear Stearns-like financial crisis with plans to raise $6 billion. But the storied investment bank, now the smallest of the major Wall Street firms, may ultimately face the same fate: the end of its independence.

Takeover rumors have dogged Lehman ever since the bank went public in 1994. A few months after the IPO, Lehman's stock tanked, prompting speculation that insurance company Travelers (TRV) would swoop in at the sale price. Investors were betting on much the same for Lehman in 1998 after the collapse of hedge fund Long Term Capital sparked a bankruptcy scare. Yet Lehman always emerged intact. "Somehow these guys never die," says Roy Smith, a professor at New York University's Stern School of Business.

Foreign Suitor?

This time around the outcome could be different. Over the past decade, Lehman CEO Richard Fuld pushed aggressively to remake the onetime bond shop into a diversified financial institution. By some measures, it worked. In 2007, fixed income accounted for 31% of revenues, compared with 66% in 1998.

But the business model of Lehman—which now dabbles in everything from bond trading to equity underwriting to M&A, and dominates none—simply doesn't work in an environment that requires either strength or size. Lehman doesn't have a distinct specialty like boutique advisory firm Lazard (LAZ). Nor does it have the heft and scale of big, commercial banks like JPMorgan Chase (JPM) and Bank of America (BAC) that are market leaders in a number of areas. "It's hard to see where Lehman fits in," says CreditSights analyst David Hendler. "Lehman needs a bigger-balance-sheet bank that can use its skill set."

The question remains, though, which financial company would step up as a potential suitor for Lehman, whose stock price is currently trading at a five-year low (BusinessWeek.com, 6/4/08). JPMorgan Chase and Bank of America have the financial muscle (BusinessWeek, 6/4/08), but the two are still busy digesting recent acquisitions. And another subprime survivor, Wells Fargo (WFC), doesn't want to get into the investment banking game. That leaves a foreign player such as Britain's HSBC (HBC) or Barclays (BCS). Although both have their own set of headaches (BusinessWeek.com, 5/13/08) from the credit crunch, the two are looking to expand in the U.S.

Rocky History

Still, absorbing Lehman would be a yeoman's task. Unlike Bear Stearns, which has a couple of strong assets in its clearinghouse and prime brokerage business, Lehman has few standouts. The once-proud, fixed income business, which has had three heads in the past three years, remains in shambles after moving aggressively into risky subprime securities. Adding to its woes, top bond executive Rick Rieder left in May to start a hedge fund.

Meanwhile, Lehman pales next to Morgan Stanley (MS) and Goldman Sachs (GS) in mergers and acquisitions, where it ranks in the middle of the pack. "They don't have a long-standing history in investment banking to thrive in this environment," says Hendler.

Then, of course, the bank has a history of rocky marriages. When American Express (AXP) purchased Lehman back in 1984, it was a poor fit almost immediately. The freewheeling style of Lehman's legendary bond traders didn't mix well with the staid atmosphere of its corporate parent. Executives clashed on everything from pay packages to critical decisions like asset sales. The two finally divorced a decade later.

Despite the difficulties inherent in an acquisition, Lehman's days as an independent firm may be numbered. Says analyst Chris Whalen of Institutional Risk Analytics: "Lehman is next. When you have a pack of dinosaurs, the slowest gets picked off."

Friday, June 13, 2008

Oil, shipping and outsourcing

![[Transport]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/P1-AL914_TRANSP_20080612182825.gif)

Stories aobut Phillips Curve

Most students of macroeconomics know the Phillips Curve — the inverse relationship between unemployment and inflation — but few know much about Alban William Phillips, the New Zealander who first identified the relationship. Though highly regarded in his time, arguably he didn't achieve the recognition he deserved, according to Robert Leeson, a visiting professor at Stanford University. He says Milton Friedman used some of Phillips' original insights to develop the role of inflation expectations and discredit the Phillips Curve. Furthermore, Phillips' poor health, in part a result of the years he spent as a Japanese prisoner of war, hindered his ability to advance and defend his research; he died aged 60 in 1975.

Friedman Still, in contemporary central banks it isn't Friedman's monetarism but the Phillips Curve (to be sure refined with the insights of Friedman and others) that infuses views of the inflation process. "A model in the Phillips curve tradition remains at the core of how most academic researchers and policymakers–including [me] –think about fluctuations in inflation," Federal Reserve Vice-Chairman Donald Kohn told a conference of the Boston Fed Wednesday. "Indeed, alternative frameworks seem to lack solid economic foundations and empirical support."

In that sense the legacy of Phillips seems secure.

Mr. Leeson writes:

In 1952 Friedman asked Phillips how to model inflationary expectations and Phillips wrote for him the adaptive inflationary expectations formula that was later used to suggest that the Phillips curve had neglected inflationary expectations. Inflation is much more serious in Phillips' theoretical model - the system becomes unstable. In Friedman's model, the worst that happens is that you return to the natural rate [of unemployment]. Phillips was in a sense more of an opponent of inflation than Friedman.

Phillips spent 3 and a half years in Japanese POW camps — he was lucky to survive. There were a lot of physical consequences — he lost his sense of taste for example. He left the London School of Economics for Australian National University in Canberra in 1967 and had a stroke shortly afterwards (he was born in 1914). He lingered on in very poor shape until a second stroke killed him in 1975 (age 60).

The Phillips Machine (1950) made him locally famous; the theoretical Phillips curve (EJ June 1954) established him as an important macro optimal control theorist; his empirical illustration (1958) and Samuelson and Solow (1960) made him widely famous; Friedman (1968) added to his fame in an adverse way.

Throughout he just pressed an as best he could with 'useful' work — he didn't engage his critics. I have speculated about this in the obituary I wrote (A.W.H. Phillips, M.B.E. (Military Division). Economic Journal 104.424, May, 1994: 605-1). But that speculation is just that — speculation.

I never really worked out how he felt about Friedman. Friedman tried to recruit Phillips to Chicago — twice. Both times, Phillips emphatically declined. That could have been for family reasons — his wife wanted to be closer to New Zealand (hence the move to Canberra).

Milton was very helpful to my research and volunteered the information about the 1952 meeting with Phillips at LSE. But Milton was also a polemical genius — he was so good at provoking his enemies. He was really taking on the Keynesiana — and the high inflation PC trade-off (which Phillips emphatically rejected) was a perfect whipping boy.

The Keynesian toleration of inflation increased until Solow pointed out ("The Intelligent Citizen's Guide to Inflation" — Public Interest 1975), a 9% inflation rate doesn't seem different from 10%. The "trade-off school", Solow argued, had a reply to the "monetary school": "Is there something qualitatively different about 'double digit' inflation? By any algebraic standards, of course, the difference between nine and 10 is no larger than the difference between eight and nine … There is no abyss, just potholes …

Inflation is their [the mixed capitalist economies] way of adapting to change. The unusually rapid rise in prices during the past year and a half may simply reflect the fact that the world has been called upon to absorb some unusually large changes. In that case, it will burn itself out".

The following Presidential term (Carter 1977-81) wiped out over 40% of the dollar's purchasing power. Inflation didn't burn itself out, but the world view associated with Samuelson and Solow (Old Keynesianism) almost did.

The irony of all this is that the person Friedman regarded as his "surrogate father" Arthur Burns was Fed chair (1970-78) while inflation was getting out of hand and Keynesians were taking the blame!

Prior to the inflationary conflagration of the 1970s, Nixon instructed Burns to "err on the side of inflation. You see to it: no recession". Burns responded that fiscal restraint was a prerequisite for a "serious fight against inflation".

For this, Burns was regarded as having "ratted" on Nixon and a vendetta developed against him. Nixon instructed his legal counsel, Charles Colson, to leak to United Press International and the Wall Street Journal the false information that Burns was planning to increase his own salary whilst pressing for wage controls for everyone else. Sources also hinted that the Fed was going to be brought under White House control.

The Watergate alumni moved on from whiteanting the integrity of monetary policy to other morally corrosive activities, and to jail.

Colson found religion and pleaded with Burns for forgiveness; Burns obliged and the two of them fell to their knees and prayed.

Thursday, June 12, 2008

A closer look at China's inflation number

CPI food component is still too high and it has been hoovering around 20% since early 2008. Be reminded food consumption in China accounts for almost 30% of personal consumption expenditure. The most recent food inflation number reads at 19.9% (see chart below).

(click to enlarge; source: NBS China and author's own calculation)

If you multiply food inflation, 20%, by food consumption weight 30%, you get food's contribution to overall inflation: 6% alone. How come the overall inflation is only at 7.7%, without even counting other big components?

My guess is that government's subsidy in gasoline makes the overall inflation look much more benign than it actually would be, if letting the market sets the price. The communication and transportation component of inflation actually has been experiencing a deflation (see chart below).

Well, aren't we having an oil shock in the world right now?

Tuesday, June 10, 2008

China's monetary policy still not tight

(click to enlarge; source: EIU, author's own calculation)

To fight inflation and not to repeat the "great inflation" (leading to deflation later, the hard landing scenario) in mid-90s (see chart below), China's policy makers need to raise interest rate quickly. And this should be done sooner than later when inflation rate is still below double digit. The temptation to allow for inflation to go even higher in order to accommodate economic growth (the so called "go-stop" policy) is dangerous and should best be avoided.

(click to enlarge; source: EIU, author's own calculation)

Richard Berner interview

Monday, June 09, 2008

Disproportional impact of oil

(click to enlarge; courtesy of NYT)

Sunday, June 08, 2008

Perfect recession indicator

One unfortunate milestone reached today was that the 12-month change in private sector jobs, before seasonal adjustment, is down 125,000 jobs. (After seasonal adjustment, there is a small increase, for some reason.)

Over the last nine recessions, dating back to 1953, that indicator has a perfect record. Every time it has turned negative, the economy is already in recession. And once it turns negative, it stays that way for quite a while. (Caution: These numbers will be revised, and this history is based on the revised figures, not the originally reported ones. But I think the revisions, when they come, are much more likely to indicate the figure went negative early rather than later.)

In December 1953, the figure turned negative six months after the recession was later determined to have begun. It remained negative for 14 months.

In October 1957, it went negative three months after the recession began, and stayed that way for 15 months.

In December 1960, the negative jobs figure came 9 months after the recession started, and it stayed negative for 10 months.

In July 1970, it turned negative 8 months after the recession began, and stayed negative for 13 months.

In November 1974, the first negative number came a year into the recession. It stayed negative for 14 months.

In June 1980, the recession was 6 months old when the negative number arrived. It stayed negative for just 6 months.

In January 1982, the negative number came 7 months after the recession started, and it stayed negative for 17 months.

In December 1990, the first negative number came 6 months into the recession, and the figure stayed negative for 17 months.

In June 2001, the recession was 4 months old. The job change number stayed negative for 30 months, the longest streak ever.

During that stretch, the figure never went negative without a recession being under way. That is not a complete coincidence, of course, since the employment figures are one factor the National Bureau of Economic Research weighs in setting recession dates.

In every case, the recession was over before the job change figure turned up. Perhaps it is interesting that the lag between the official recession end and the first 12-month increase in private sector jobs was significantly longer than in earlier recessions. The lag was one year after the recession ended in March 1991, and two years after the most recent recession ended in November 2001.

If we assume that this year falls within the previous parameters, then the recession started sometime between May 2007 and March 2008, with October 2007 the most likely. Based on other data, October is probably the earliest date that the recession could have begun.

Again assuming the previous data is predictive, the last negative job number will arrive between November 2008 and November 2010, with August 2009 the most likely month.

Friday, June 06, 2008

What if Trichet truly admires Volcker?

But maybe one fact was neglected. Unlike the Fed's dual mandate, ECB has the single mandate of fighting inflation. This makes sense especially when I consider: What if President Trichet is a truly admirer of Paul Volcker, a.k.a inflation fighter to bring down inflation no matter what?

Will dollar's further downfall and the possibility that Gulf countries unpeg dollar eventually pressure Bernanke to adopt similar policy stance? Let's wait and see.

But bear in mind, monetary policy 101, something we have learned in the past several decades, tells us maintaining price stability is the No. 1 priority for the central banks. Yes, no matter what.

Time to declare: Oil Shock 2008

Jim Hamilton has these two graphs to share:

Oil crises in 70s made the economy today less reliant on oil, but don't take it for granted.

Crude oil going crazy

May Unemployment rate jumped to 5.5%

The data, which included a fifth-straight drop in nonfarm employment, should take financial-market expectations of Federal Reserve rate increases as soon as this fall off the table.

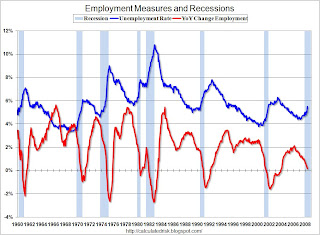

The below graph shows the unemployment rate and the year-over-year change in employment vs. recessions.

(click to enlarge; coutesy of CR)

Note the current recession indicated on the graph is "probable", and is not official.

Einhorn on Lehman Brothers

Wednesday, June 04, 2008

Commodity-Price Scapegoats

Commodity index funds are especially vulnerable politically. They are a big target – reportedly, there is about $260 billion invested in them currently. Among their largest investors are retirement funds for government employees and teachers, which by their very nature are subject to political pressure. For example, the organized labor lobby is already trying to get states to make their funds to stop investing in private equity deals in companies that won't employ union labor.

...

The evidence against the index funds is circumstantial at best: Commodity prices have soared over the same recent period that commodity index funds have rapidly grown. So the index funds must have caused it.

But coincidence isn't causation. And such causation that can be shown to exist actually runs the other way: Rising commodity prices cause the dollar value of commodity index funds to rise, just as rising stock prices would make a stock index fund more valuable. This accounts for nearly half the reported growth in commodity index fund assets this year. But if commodity index funds are such a powerful influence on prices, how can one explain the fact that not all the commodities in the GSCI have risen?

Unlike other commodities buyers, index funds never take physical delivery of commodities to store or consume them. They are investors, not hoarders. They don't divert any supplies from the markets. When their futures contracts near expiration, they sell them and replace them with longer-dated contracts. Thus, once their positions are established, they are perpetually both buyers and sellers in equal proportion.

Bernanke at Harvard: Not the 70s

He echoed similar view as Janet Yellen, that today's situation is very different from 70s, notably, there is no wage-price spiral and inflation expectation remains low albeit increased quite a bit recently.

Read analysis from wsj here, video of the speech here.

Oil and sushi

Sushi is in danger of falling victim to high oil prices after fishing industry groups warned that a third of the world's long-line tuna fleet – the ships that catch the high-grade tuna used in the Japanese dish – could remain docked this year as soaring fuel costs make fishing unprofitable.

Tuesday, June 03, 2008

Realities and elusions

What to take away? 1) More trouble to come for US banks; 2) Asian inflation serious macro concern, the biggest challenge for Asian economies since 1997.

Soros give four reasons for high oil

First, the increasing cost of discovering and developing new reserves and the accelerating depletion of existing oil fields as they age. This goes under the rather misleading name of "peak oil".Second, there is what may be described as a backward-sloping supply curve. As the price of oil rises, oil-producing countries have less incentive to convert their oil reserves underground, which are expected to appreciate in value, into dollar reserves above ground, which are losing their value. In addition, the high price of oil has allowed political regimes, which are inefficient and hostile to the West, to maintain themselves in power, notably Iran, Venezuela and Russia. Oil production in these countries is declining.

Third, the countries with the fastest growing demand, notably the major oil producers, and China and other Asian exporters, keep domestic energy prices artificially low by providing subsidies. Therefore rising prices do not reduce demand as they would under normal conditions.Fourth, both trend-following speculation and institutional commodity index buying reinforce the upward pressure on prices. Commodities have become an asset class for institutional investors and they are increasing allocations to that asset class by following an index buying strategy. Recently, spot prices have risen far above the marginal cost of production and far-out, forward contracts have risen much faster than spot prices. Price charts have taken on a parabolic shape which is characteristic of bubbles in the making.

Zhou says hot money into China exaggerated

Source: China Daily

U.S. Federal Reserve's interest rate cuts have helped increase liquidity, but have also led to rising prices in commodities, Zhou Xiaochuan, governor of the People's Bank of China, said on Friday.

The central bank governor said this has affected the anti-inflation policies of emerging markets.

Zhou was speaking at a conference following the release of a report by the Commission on Growth and Development, an international organization that focuses on policy consultation in emerging markets, and provides reference for aid programs.

"The U.S. Fed has significantly reduced interest rates on the other hand, global commodity market prices have risen. A lot of developing countries are now suffering from rising inflation," Zhou said.

The central banks of the world should cooperate more closely to tackle the inflation problem, he said.

On another issue, he said experts may have exaggerated the amount of "hot money" which has flowed into China.

"I've always held that it is not a comprehensive approach to simply look at trade surplus and FDI (if you calculate speculative capital inflows) you have to make a comprehensive check of the overall international balance of payments," he said.

Hot money, which triggered the Asian financial crisis in 1997, is being carefully watched in China, especially with the appreciation of the yuan and high inflation.

China's reserves, the world's largest, have increased rapidly this year. By the end of March, the reserves stood at 1.68 trillion U.S. dollars, increasing by 154 billion follars in the first quarter.

During the same period, China's trade surplus was 41.4 billion dollars while the FDI was 27.4 billion dollars. Many analysts suspect the 85 billion dollars gap was hot money that flowed into China in anticipation of the yuan appreciating.

In April, the stockpile grew by a further 74.46 billion dollars, with the total reserves swelling to 1.76 trillion dollars, a Reuters report said, citing a source familiar with the data.

The increase in the reserves in April was about 50 billion dollars, more than the total of China's trade surplus of 16.7 billion dollars plus FDI of 7.6 billion dollars.

However, Zhou said many of the various accounts in the country's balance of payments could contribute to the expanding foreign exchange reserves.

"For example, we also have services trade and income on the current account (that affects the level of the reserves). And the financial markets are increasingly more sophisticated now," Zhou said, referring to the complicated currency derivatives that can affect the level of foreign exchange reserves.

Bernanke links falling dollar to rising inflation expectations

Good thing about high oil price

General Motors CEO Rick Wagoner said the company plans to cease production at

four North American plants that build pickups, SUVs and medium-duty trucks amid

the sharp rise in oil prices and the "significantly more difficult" auto market.

The company plans to fund its Chevy Volt electric vehicle for commercial

development and hold a strategic review of its Hummer brand. Auto makers are

scheduled to post monthly sales results later today.

Monday, June 02, 2008

Robert Barro interview

Robert Barro's bloomberg interview (audio mp3) on monetary policy, economic growth, China's development experience, economics of religion, etc.

Currency-led commodities bubble

Expressed in gold, prices of oil and wheat haven't changed much.

And the correlations between commodities and US dollar increased to over -0.9 recently.

I am sympathetic to Steil's view and I see some parallel between the housing bubble and current commodities bubble.

In 2001, when economy was in recession and Greenspan Co. cut rates 11 times to 1%. Investors, lack of investment opportunities after dot.com bubble, all flocked to housing sector. Actually, housing was probably the only bright spot then.

In current cycle, Bernanke co. cut rates in a similar fashion, prolonging dollar's downturn, and investors again poured their money into the "safe haven" as a hedge both against inflation/US dollar and meager investment opportunities in a time of credit crunch, and twin crisis in both housing and financials.

Sunday, June 01, 2008

Yellen speech on economy and inflation

She somewhat shares the worry that "even if the direct influences of commodity prices on inflation eventually dissipate, they could still cause trouble...higher inflation could become built into inflation expectations and become self-perpetuating". But she thinks so far there is no evidence for such case, especially inflation is very unlikely to pass on to the wage this time, causing a wage-price spiral like the 70s.

The full speech can be read here and her presentation slides here. Below are two nice charts from her presentation.

Rent or buy? you calculate yourself

Hot money pouring into China

"If this is true that means that reserves grew in the month of April by $74.5 billion, the biggest one-month reserve jump in China’s history (and probably in the history of the world)...

To get a sense of scale, in 2006 reserves were up $247 billion for the whole year. This, at the time, was a number guaranteed to shock. No central bank in history has seen reserve growth at anywhere near this scale. Nonetheless in 2007, the growth in reported reserves nearly doubled over the previous year -- $462 billion – and more than doubled if we backed out a series of transactions that reduced headline reserve growth but had no net impact on the monetization of currency inflows..."

(click to enlarge, courtesy of Michael Pettis)

Inflation expectations highest since 1982

More worrisome, consumers, on average, expect prices to increase 5.2% in the next 12 months, the highest level for an expected rise since 1982. Meanwhile, the gap in yields is widening between Treasury bonds that are indexed to inflation and those that aren't, suggesting investors also think prices will keep climbing.

(click to enlarge. source: FRED)

Don't be fooled by GDP revision in short term

I'd like to remind readers that GDP is a series subject to a lot of revisions (and in any case, NBER looks at a lot of other series). To that end, I depict below what we thought GDP was doing at the end of May 2001 [1], [2]. Figure 2: Real GDP (Ch.2000$, SAAR), annualized quarter-on-quarter growth rates from May 2008 release (blue), from May 2001 release (red), from July 2001 release (green). NBER defined recession highlighted gray. Source: BEA via FRED II, ALFRED, NBER, and author's calculations.Note that even at the end of July 2001, we still thought 2001Q1 growth was positive, and thought the same of 2001Q2 as well... So I'm more in agreement with Jeff Frankel than with Carpe Diem.The reason why many suspected a QI turning point in the first place is employment, which is virtually as important an indicator to the NBER BCDC as is GDP. Jobs have been lost each month since January. Total hours worked is my personal favorite, because in addition to employment it captures the length of the workweek, which firms tend to cut before they lay off workers. ...

Figure 2: Real GDP (Ch.2000$, SAAR), annualized quarter-on-quarter growth rates from May 2008 release (blue), from May 2001 release (red), from July 2001 release (green). NBER defined recession highlighted gray. Source: BEA via FRED II, ALFRED, NBER, and author's calculations.Note that even at the end of July 2001, we still thought 2001Q1 growth was positive, and thought the same of 2001Q2 as well... So I'm more in agreement with Jeff Frankel than with Carpe Diem.The reason why many suspected a QI turning point in the first place is employment, which is virtually as important an indicator to the NBER BCDC as is GDP. Jobs have been lost each month since January. Total hours worked is my personal favorite, because in addition to employment it captures the length of the workweek, which firms tend to cut before they lay off workers. ...

![[chart]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/MI-AQ864_ABREAS_20080615185232.gif)

![[Milton Friedman]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/HC-GF440_Friedm_20061116115638.gif)